With Javelin, Sufjan Stevens creates an intricate, gorgeous rumination on love, grief, and perseverance.

Sufjan Stevens, in his multi-decade recording career, has never been confined to one sound. Though he may be best known for the chamber pop he put out in the 2000s, he’s worked in a variety of genres—classical, ambient, electronic and, perhaps most notably, singer-songwriter. With Javelin, his 22nd album release and tenth non-instrumental solo album, Stevens has finally created a stylistic synthesis of his past endeavors.

Stevens returns to the flute-heavy renaissance-faire sound that’s been with him since his first official release, A Sun Came. Unlike A Sun Came, though, it feels purposeful. These whimsical flourishes bring levity to otherwise devastating songs like “Will Anybody Ever Love Me?” and build upon the religious ideas put forth in the lyrics. The presence of the backing chorus, which has accompanied Stevens on many of his previous endeavors, deepens the lyrical meaning of these songs—as much as Stevens expresses ideas of loneliness, he is bolstered by a crowd.

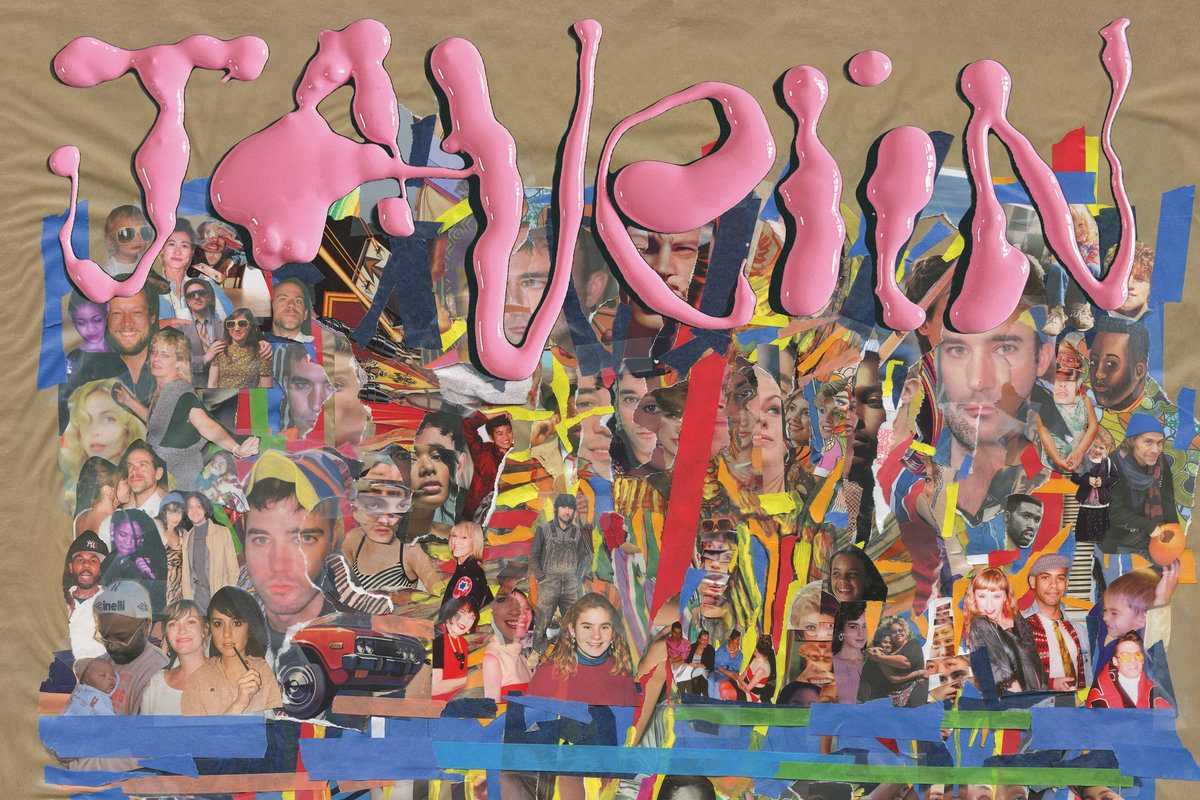

Javelin, both stylistically and in cover art, most immediately resembles Stevens’ 2010 EP, All Delighted People. It is similarly grand in its scale while still maintaining a stripped-back folkiness. Its second song, “Enchanting Ghost,” is echoed in “Genuflecting Ghost,” an equally mournful plea to a lover. Despite this, it’s 2015’s Carrie and Lowell—a soft, devastating rumination of the death of Stevens’ mother—that is most significantly called to mind. Javelin, similarly, centers on loss; Stevens has dedicated the album to his partner, Evans Richardson, who passed away in April.

Stevens approaches loss from a place of impermanence, of living inside grief and memory simultaneously. Many of its songs are written as addresses, sung in first person to a vague “you.” Stevens paints a picture of a relationship in its whole, not shying away from the uglier parts. “Javelin (To Have and To Hold)” is a rumination on regret; “So You Are Tired” is, in essence, a break up song, lamenting the loss of patience. In a blog post discussing the album, Stevens wrote, “I know relationships can be very difficult sometimes, but it’s always worth it to put in the hard work and care for the ones you love.” Javelin centers on not just on love, but on the struggle that comes with it. For instance, on “Shit Talk,” the album’s longest, grandest song, the lines “I will always love you / I don’t want to fight at all” circle each other, building to a euphoric carousel. The song then slowly simmers out, dissipating into sustained notes and wordless vocals. Sonically, it replicates the feeling of fighting, of turmoil, and of resignation.

Despite its heavy subject matter, Javelin contains an incredible lightness, both sonically and lyrically. Tracks like “A Running Start” portray a genuine, consuming kind of love. Though not a new subject matter for Stevens, he has seldom written about it so directly. He sings the word “kiss” over and over throughout these ten songs. He’s used this word sparingly in the past—it’s almost too affecting—but here it finds a new potency in its repetition. In “A Running Start,” a kiss is something to come, something given. In “My Red Little Fox,” it’s blisteringly present, acting as an aching refrain. “Genuflecting Ghost” ends with the line “I kiss no more.” In mixing tenses, Stevens creates a warped sense of time. These songs do not follow a linear progression; they tell a larger, cyclical story. Javelin portrays not just what was, but how it lives now, how it will live on.

The idea of forever permeates this album. From the opening track, “Goodbye Evergreen,” Stevens dives into loss, into how something that feels permanent can end so completely. Javelin is an album of contradictions: of forever and impermanence, of heaviness and lightness, of love and heartbreak and harm and loss.

The album ends on a note of clarity. Stevens’ cover of Neil Young’s “There’s a World” is disparate from the rest of the album in its instrumental simplicity. With the final line “All God’s children, in the wind, take it in and blow real hard,” it offers gratitude, optimism. That Stevens can maintain his sense of wonder and love for the world in the face of so much pain is remarkable. Javelin is a testament to perseverance, a beautiful, tender document of the hardship of living, and a reminder to take stock of what you have.

Grade: A+