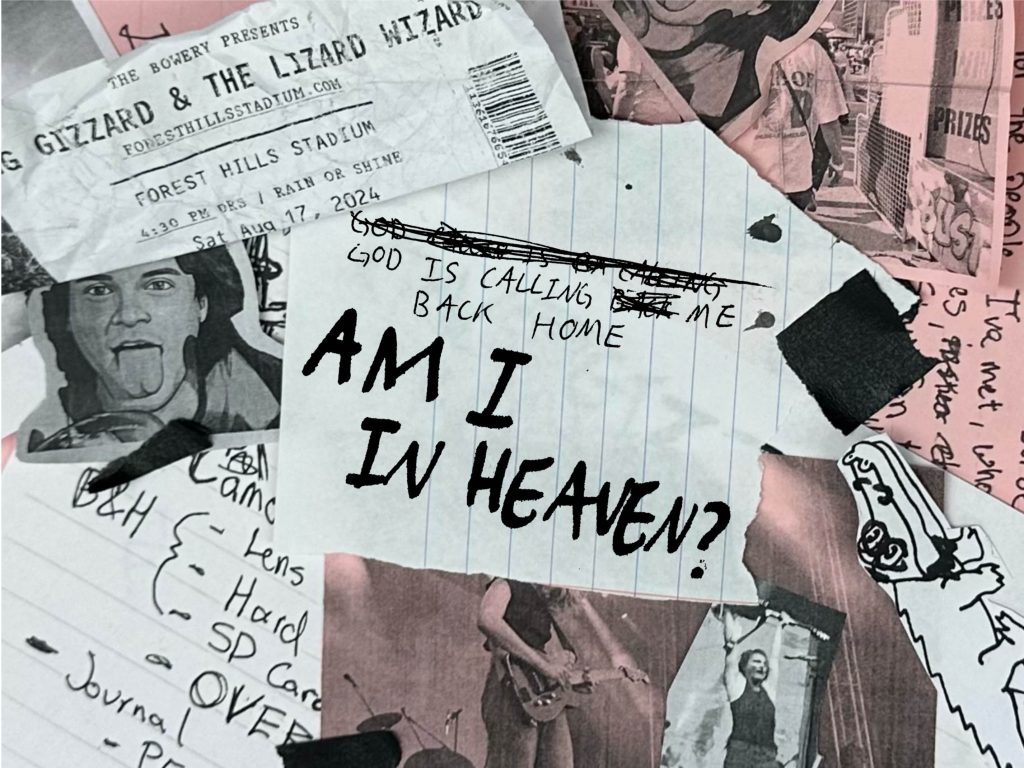

At the tail end of summer, 2024, two STATIC staff writers embarked on a 15-day road trip and followed King Gizzard and the Lizard Wizard to ten cities on their North American tour. To be serialized weekly in STATIC across the next six weeks, God is Calling Me Back Home is a tour diary and a memoir, as well as an examination into the material and spiritual remnants of psychedelic bohemia.

PROLOGUE: A SONG FOR THE LAST ACT

September 1st, 2024

GREENVILLE, SOUTH CAROLINA

I feel silly and sick. I’ve been off tour for 2 days now, and I don’t know what to do with myself. I threw up from anxiety today, which hasn’t happened in a long time. I used to do that almost everyday my senior year of high school, worried sick about my girlfriend. Now, one day before the start of my junior year of college, I am just as worked up. I miss my family. I miss my room. I miss my innocence. I didn’t realize how alone I have felt for 2 years straight now, how lost and confused I have been.

I saw a painting by Henry Peters Gray at the Detroit Institute of Art, a little over a week ago now. It showed a veiled, nude woman holding a mirror, revealing the reflection of an upside down world, the sky where the ground should be and vice versa. A small placard displayed the painting’s title, “Truth.”

Something struck me at that moment. The woman’s soft smile seemed to call me out, calmly scolding me for confusing mere reflections of consciousness for my true mind’s eye. I have seen everything upside down for longer than I can remember. I have become a slave to my senses. I sit in my childhood bedroom, listening to “I See Myself” by Geese, and I begin to sob. I don’t know what else to do. I remember why life is beautiful.

For two weeks, I thought of nothing but my friends, family, and my favorite thing in life, which has always been and will forever be music. I will never be the same. My grandmother’s mantra has always been, “But by the grace of God go I.” Today, I begin to truly grasp what she means. I reflect on the many powers outside of my control that acted upon me on this trip, and how they ultimately delivered me back to the comfort of my Mother and Father.

At long last, I am back home, I am safe, and I am surrounded and filled with Love. I take a deep breath, and for what feels like the first time in years…all is quiet.

AM I IN HEAVEN?

August 18th, 2024

NEW YORK CITY, NEW YORK

I look out into a swarm of weirdos and spot someone with bronze curly hair and a black, “NEW YORK FUCKING CITY” shirt . . . there’s J-Mac.

He’s sitting at one of many picnic tables, all littered with colored fabrics in the overcast backyard of a pub in Forest Hills, Queens. Displayed on his table is a white t-shirt with a sorcerer and crystal ball announcing: “KING GIZZARD AND THE LIZARD WIZARD, 2024 SUMMER TOUR.”

When J-Mac first asked me to “go on Gizz tour” with him, I was a bit confused. I knew that he was the hippie type, but I didn’t know that there was that scene surrounding this band: chasing every set, selling bootleg merch, meeting new people, peace, love, drugs…it all sounded very exciting.

I wrestled with the decision for several months after, worrying about time and money and all the things that could keep a person from doing what they please. Yet something deep inside of me knew that I had to do this.

I admit, my mind immediately turned to the counterculture of late 1960’s America, a historical moment which has been continually graverobbed for inspiration and aesthetic; I’m guiltier than most. It’s the reason why the documentary “Woodstock 99’” was so impactful to me. The greed, rape, and fire that plagued the attempt at “3 more days of peace, love, and music,” serves as a grim but firm refutation of flower power politics. I tend to meet any attempt to revive that spirit with cynicism.

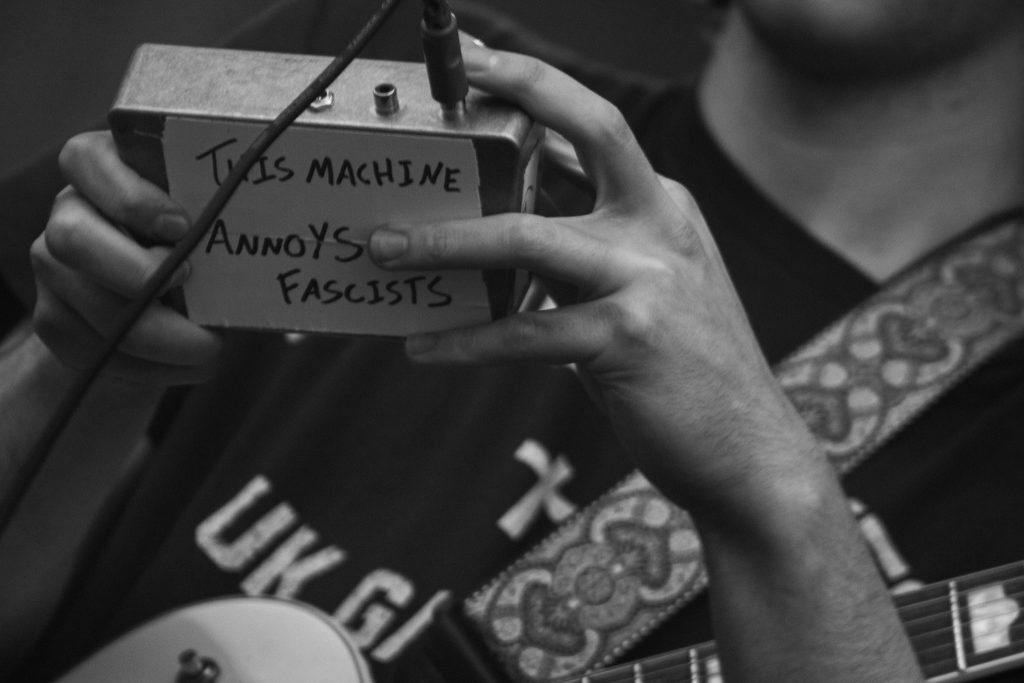

However, when I consider why I feel called to follow King Gizzard and the Lizard Wizard on tour, a few things give me hope that the same spirit that flowed from the Bohemians to the Beats might be at work again. Unlike acts like Phish and Dead & Company, Gizzard feels much more representative of the compassion and resilience the original era allegedly embodied. Their music calls attention to animal cruelty and environmental rights, and they performed in drag for one of their five nights at The Caverns in Tennessee in protest of anti-trans legislation.

Gizzard released their first full length album in 2012, and in the twelve years since have released 25 more. This sort of artistic efficiency would be impressive enough on its own, but they refuse to repeat themselves, exploring different genres, instruments, and atmospheres on each album. While the band has been pumping out records for over a decade now, their heap of hippie-dippie disciples is a fairly recent phenomenon.

This seemed like the perfect opportunity to witness the type of culture that I used to only read about firsthand, only in 2024. I was excited to discover how the modern age has influenced the nature of this American tradition and add myself to a long lineage of people who love rock & roll religiously.

J-Mac has already firmly cemented himself in this tradition, having followed Dead & Company on their final tour the summer prior. Just a month ago, he traveled across North America to play guitar for the New Jersey shoegaze band High. He started his Gizz tour run 3 days before me in Washington D.C. for the opening show of the 2024 North American Tour, as well as attending the first Three-Hour Marathon Forest Hills show last night.

Tonight, I’m joining him for the second New York show, and we will travel across thirteen states and one province to see ten King Gizzard shows together over the next two weeks. Like a true Deadhead, he will be vending self-made merchandise before the shows at fan-organized meetups to help keep us on the road. This is where I first find him on a cloudy afternoon in Queens.

I walk over and give him a big hug. I sit at the table, which is displaying a stack of his white King Gizzard shirts and a few scattered light green lighters, declaring simply “gizz” in the Brat font. A bootlegger next to us sits and continues his conversation with J-Mac.

He is a scraggly, lanky hippie with long straight black hair, a scruffy beard, and one of his purple and green King Gizzard Tie Dyes. Originally from Florida, he studied Chemistry before dropping out to follow King Gizzard on tour. “When I got in line at 7 a.m. at the Anthem in D.C on Thursday, I knew that I was back home,” he tells us, seemingly rushing to get the words out, overwhelmed with excitement and passion. He asks J-Mac if he wants any mushrooms for the show tonight. “I’m actually sober,” J-Mac politely declines.

The same night that J-Mac asked me to go on tour with him, we discussed his sobriety in depth for the first time. He told me about the Wharf Rats, a support group for sober Deadheads. They organize gatherings during set breaks, pass out Narcan on tour, and provide community for fans in recovery. It intrigued me. I wrongly assumed that this sort of lifestyle was codependent with heavy drug use. It is beautiful that the joy of music and community is enough for some people and I am excited to share this experience with one of them.

I admit, I feel a tinge of temptation at the realization that it really would be that easy to score psychedelics among this crowd. “You can do whatever you want at the shows,” J-Mac had told me in the weeks prior, sensing my curiosity, “I just don’t want to travel with any drugs in the car.”

As the fan meetup dwindles, we pack up and head towards the closest thing that we will have to a home for weeks. J-Mac opens the trunk of a gray Toyota Sienna riddled with Grateful Dead Steelie stickers; one reads, “THICC DADS WHO VAPE FOR JERRY.” The inside floor is littered with supplies: Slim-Jims, Pop-Tarts, and an assortment of ramen. We both grab water and chat outside the van. We walk to the stadium while J-Mac tries to sell a few more shirts. A cop wordlessly shoos him away, so we try to find the box office.

Thanks to the savviness of the good people at STATIC Magazine and generosity of Panache Booking and Pitch Perfect PR, we will have a ticket and a photo pass for every single show on our two week tour run. As we approach, the sky darkens and it starts to gently rain. I am getting nervous. I took a photography class in Sophomore year of high school, and have used my camera very infrequently since . . . Undeterred, I decide that I will hopefully trial-and-error my way into some cool shots over the next few weeks.

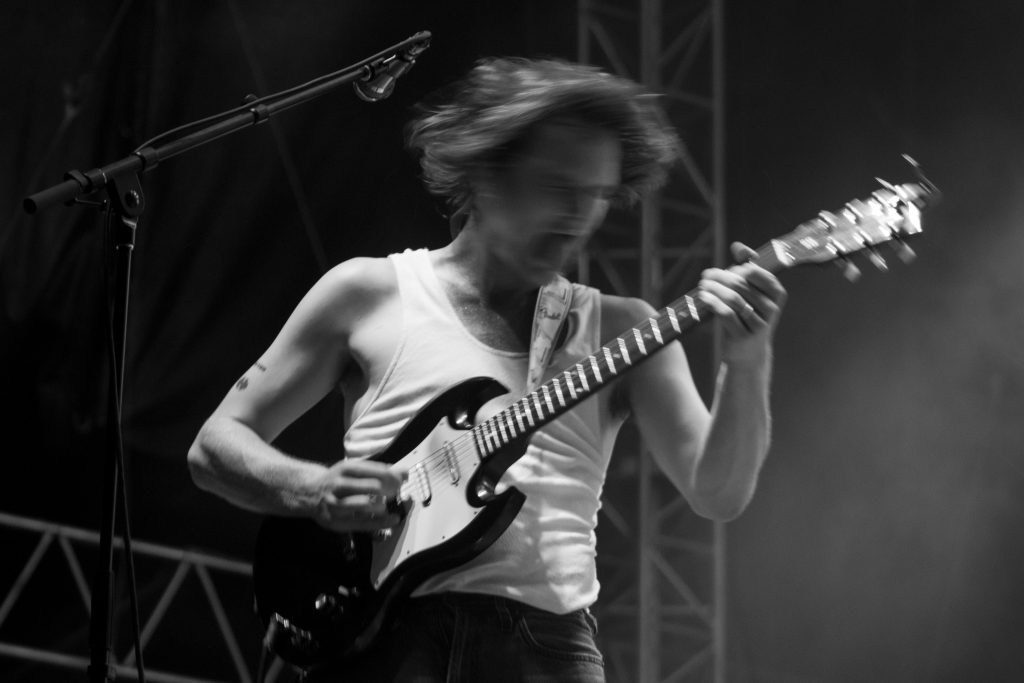

As I make my way up to the photo-pit, the weather worsens. I drape myself and my bag in a poncho someone was kind enough to give me. The small space between the stage and the rail is packed full of people who seem more confident and competent than me. Geese takes the stage, the NYC based band who will travel with Gizzard for the entire first leg of this tour. Their music is charming and loud . . . really loud. I lost my earplugs on the train, and the massive PA’s assault me with guitars, drums, and lead singer Cameron Winter’s slightly sarcastic voice. Eventually, I see a pair of used foam earplugs sitting on the edge of the stage, and shove them into my ringing ears.

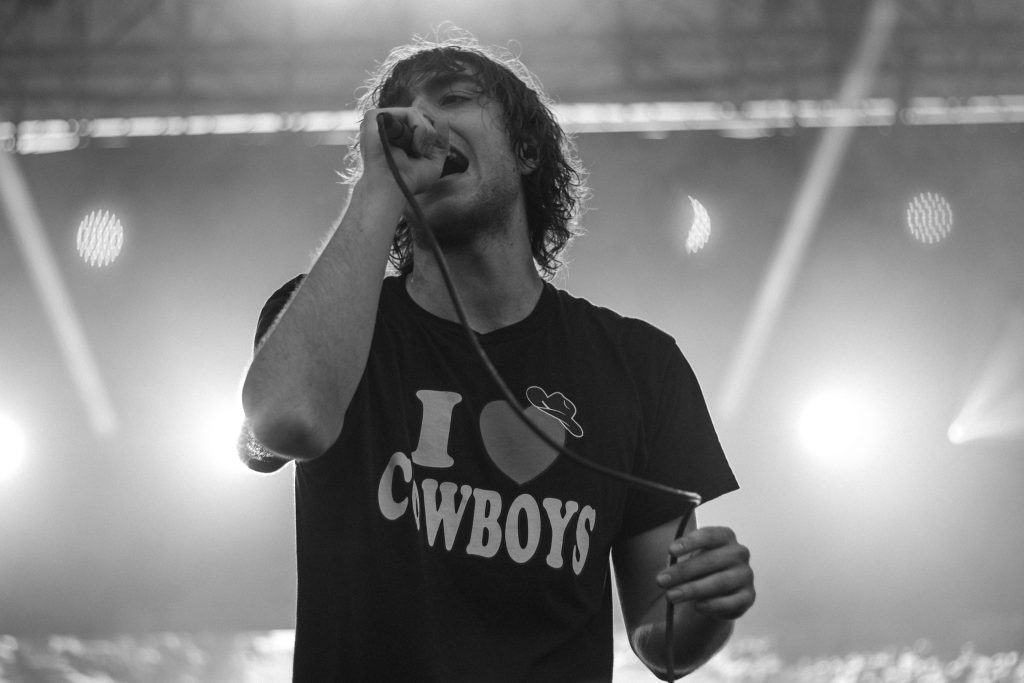

By the time the opening set is over, my insecurity has been replaced with excitement and awe. When the members of King Gizzard walk on stage, the stadium begins to scream. Lead singer Stuart Mackenzie approaches the microphone, a flute in his hand. He tells everyone to take a moment to look around. I turn to the crowd and receive the massive roar that the stadium full of fans offers in return. A semicircle of American flags flap in the distance, dancing in the storm.

Stu lifts his flute to his mouth and, with his first note, fires the starting pistol for tonight’s marathon. A few minutes into the extended jam of “Hot Water,” I see JMac’s curly hair and contorted face floating above the audience, before tumbling over the rail into the photo pit. He grins madly, pats me on the shoulder, and darts back into the crowd. I am immediately swept up by the collective of the photographers, the crowd, and the band.

Just an hour or so in, I begin to understand what might attract this band’s cult-like following. The band make playful quips at one another and the audience as they dance in and out of their many albums, all accompanied by trippy visuals performed live by longtime collaborator Jason Galea. During “Billabong Valley”, keyboard player Ambrose dons a cowboy hat to sing his verse, jumping into the crowd and surfing around on top of an inflatable alligator before strutting back on stage and mooning the crowd briefly.

The band’s energy grows as the night darkens, though mine dwindles. Even as I tire, I am aware that this is the most fun I have had in a long time. I get to do this nine more times over the next two weeks. Still, when the show ends, after a 13 minute long rendition of “Am I In Heaven?,” I feel a strange sadness as the band throws drumsticks, setlists, and kisses out to the crowd. I fight my way through the flood of people exiting, struggling to find J-Mac outside. Through the crowded chaos, I see a white shirt shining high in the night like the Star of Bethlehem.

He’s with our friend Sevin, and I catch up with them while J-Mac sells a few more shirts. We hop back in the van and listen to Geese on the ride back towards Manhattan. I spent my summer riding the subway for hours everyday, so there is something distinctly liberating about watching the staggering skyscrapers grow through the backseat window of a car. We cross the Williamsburg bridge, drop Sevin off in the Lower East Side, then split at my uncle’s apartment in Midtown where my parents are staying this week for my sister’s freshman year move-in at The New School. He pulls the van over on 6th Ave, and we plan to be on the road by noon the next day. I walk inside, buzzing.

After delivering a quick recap of the concert to my Mom, I lie down on the couch and look out the window at the skyline and the H&M tower. Two years ago, we stayed in this same apartment the week before I began my freshman year at NYU. I remember staying up until the sun rose, thinking about my girlfriend, thinking about how I would survive living in the city, thinking about if I was making a terrible mistake… thinking, thinking, thinking.

The memories start flooding back, so I open my laptop and look through the pictures I took today. Soon, the sun begins to rise and birds float through the tall buildings, seemingly unconcerned with the manmade monstrosities confining their flight. As I watch the concrete slowly soak up the natural light, I wonder what could have possibly led me here . . . and where I am about to go.

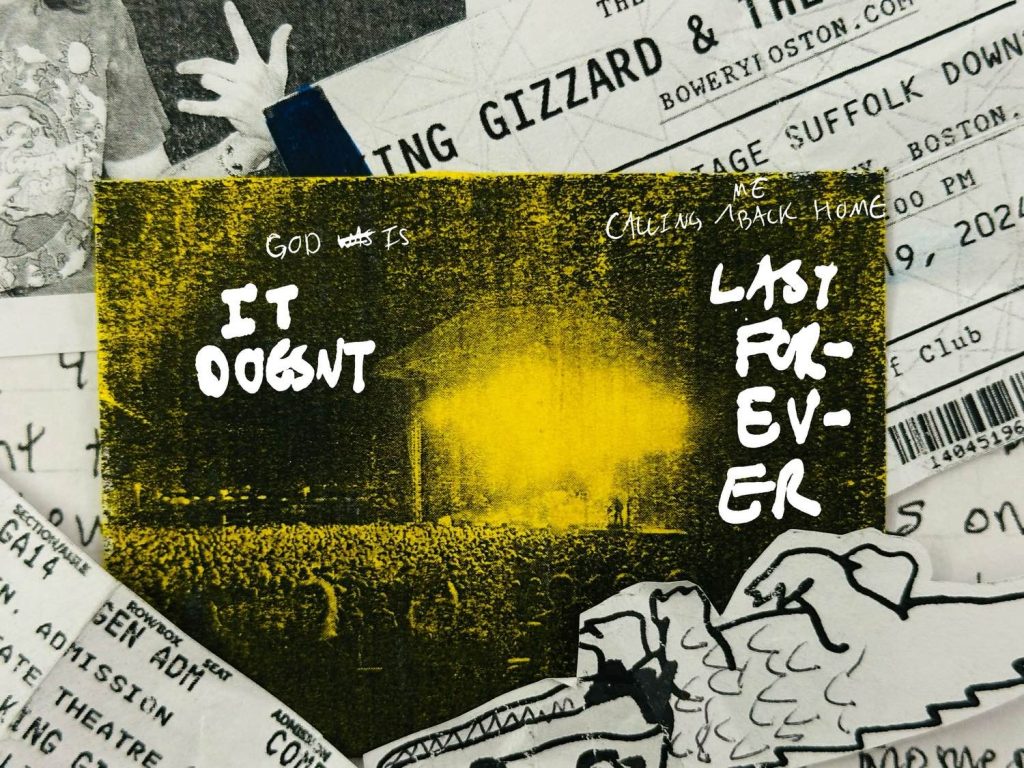

IT DOESN’T LAST FOREVER . . .

August 19th, 2024

BOSTON, MASSACHUSSETS

I wake up around noon to J-Mac and Catie standing over me, grinning. “Good morning sunshine,” they tease me.

We had arrived in Boston late last night after hours of driving through Connecticut flash flood warnings, listening to live Grateful Dead albums and talking about King Gizzard and The Lizard Wizard. As heaps of water crashed down on our windshield, I began to suspect that the specter of the Dead will haunt me on this tour.

J-Mac and I talked for a long time that day about the differences between the two bands. J-Mac claimed that seeing Gizz is nothing like seeing the Dead. For him, that music is a spiritual experience and an American tradition. I agree that there is something uniquely American about the Grateful Dead, whose radical roots shriveled with age.

Yesterday’s psychedelic symposium lingers as I crawl out of bed and join J-Mac at the kitchen table. Catie makes us eggs and coffee. With an unfamiliar experience ahead of me, I am very thankful for the comfort of close friends. Catie, who I have known since the first grade, is starting her final year of study at Emerson College . . . she doesn’t love it, but she is doing well. She lives in a two bedroom apartment on a quiet street, about a 20 minute walk from campus. My parents call me to ask if we made it into town okay. They talk to Catie for a long time.

After a lazy day, we all put on Grateful Dead t-shirts and return to the van. It’s about a thirty minute drive to Suffolk Downs, an old horse racing track near Logan Airport. Parking is $30 dollars.

“Is there any sort of ‘I’m really cool’ discount?” J-Mac asks the attendant, hanging his wide grin out the window.

“Not here buddy,” the man replies in a thick, unamused Boston accent.

J-Mac forgot his camera at the apartment, so he borrows mine for Geese’s set while I watch with Catie from afar. J-Mac is showing us his pictures afterwards when stagehands begin wheeling out a giant table filled with keyboards and MIDI controllers. J-Mac’s eyes widen: “Holy shit, they’re bringing out the synths . . .”

The synth table has not made an appearance at any North American show so far. Excitement bubbles in the crowd. I take the camera, and J-Mac and Catie merge into the mass. The band crowds around the table, and slowly layers of bass and arpeggios start to rise. Stu dons a green bucket hat and sings the opening lines to “Gondii” into a vocoder. His robotic voice floats over the sounds of circuitry.

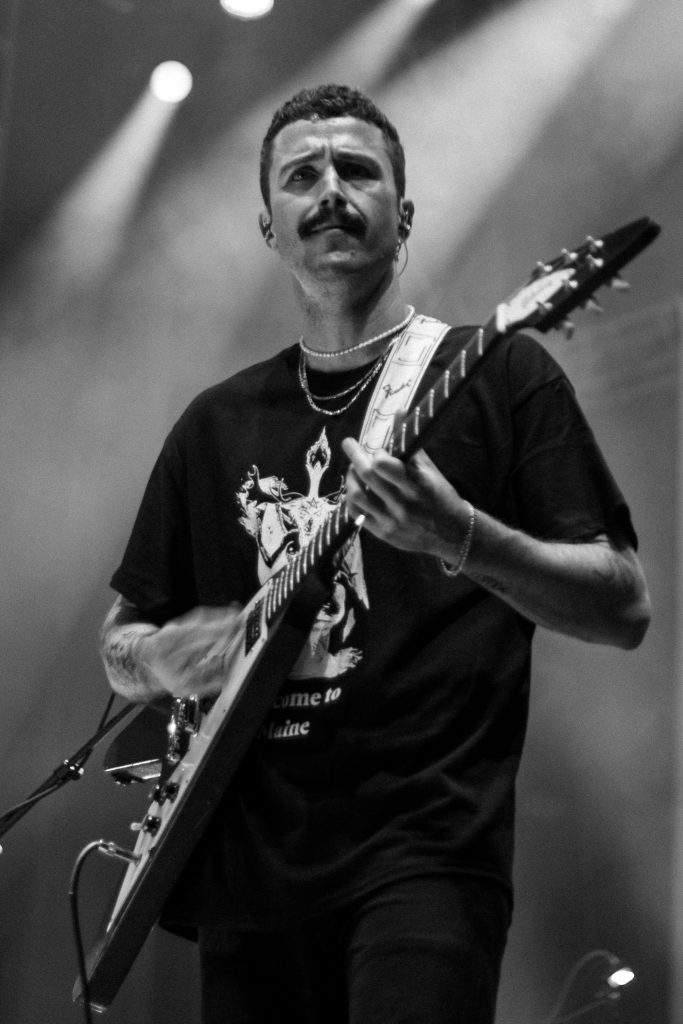

They start to occasionally wander away from the table as they move into “Change,” “Extinction,” and a personal favorite of mine, “Grim Reaper.” Ambrose raps over the synthy clavinet groove before the table is wheeled off entirely. “You gotta rip the band-aid off sometime,” Guitar player Joey Walker quips. They quickly launch into a trashing metal track “Supercell.”

This whole time someone has been holding a big tarp. Joey starts to read it out loud. Timmy, the tarp-bearer, was supposed to be here with his best friend, a pilot who passed away recently. Timmy wants to play the guitar part to his friend’s favorite song Perihelion in memory.

“That sounds pretty fackin’ good,” Joey says, and security pulls him over the rail and onto the stage. Timmy thanks the band for letting him interrupt their set.

“Anyone here who’s with a friend tonight, just make sure you cherish them,” Timmy says. “It’s a really hard lesson to learn that this moment won’t last forever.”

I think of J-Mac and Catie standing back in the pit somewhere. I am very aware of my breathing. Joey, free from his guitar, parades around the stage while Timmy shreds in his late friend’s King Gizzard shirt. It sounds like a stone rolling away from an empty tomb.

Soon after Timmy re-joins the crowd, the band launches into “Gila Monster.” The past few days, J-Mac has been wearing a beaded bracelet spelling out the song’s title, and I wonder where he is. As if my thoughts summon him, he appears next to me, wide-eyed and disturbed. He holds up his phone, and I read a text from his ex-girlfriend. I give him my camera again, so that I can relax and he can distract himself. After the show, we meet up with Catie and snack on cashews quietly in the van. J-Mac is still shaken.

When we arrive back at the apartment, Catie’s roommate is also having a rough night and needs some privacy. J-Mac and I head outside. We sit in front of one of the many colonial style brick row homes on the block, and talk about being on the road. I ask about his experience this summer, playing guitar for High all across the continent.

“This is all I want to do,” he tells me. A bunny hops across the empty street. “Just travel and chase music.”

We walk back inside. The situation has settled; Catie and I discuss the drama in hushed tones in her room. She starts to vent: she dislikes her major, she dislikes her school, she dislikes her city . . . “Maybe I just need an adventure,” she tells me. I understand.

After a solemn summer in New York, I am relieved to be anywhere else. It’s easy to get stuck in a city, gummed up by the same sights and sounds.

I think about all the places that J-Mac and I will travel to in the coming-days. I’m excited . . . but this has been the easiest part. I stayed with my family in New York and one of my closest friends in Boston. Many nights of couch-crashing and cozying up with a greasy hippie in the back of the van await me. The greasy hippie knocks on Catie’s door. He walks in looking sad and defeated.

“I’m tweaking,” he sighs.

We talk about the text – she wants to talk when he’s back in New York. Catie reminds him that he doesn’t have to do anything that he doesn’t want to. I share my own stories of past paranoias and unhappy hauntings. J-Mac goes back to sleep and seems a little better. Catie starts to play an episode of Good Mythical Morning on her phone. I close my eyes, and it feels like just a few seconds pass before I am shaken awake by J-Mac in the morning.

“Yo, we gotta go in 20.”

THE CLOSING OF THE FRONTIER

August 20th, 2024

PORTLAND, MAINE

“WELCOME TO NEW HAMPSHIRE // LIVE FREE OR DIE,” a road sign reads as we zip up I-95 North. The New England wilderness dances in and out of focus through the window of the van. I wonder if I’m living free right now . . . I don’t want to die.

Right before I left for the tour, I watched the film Easy Rider, starring Dennis Hopper and Peter Fonda as Billy and Wyatt. On a pot-fueled motorcycle trip from Los Angeles to New Orleans, the two hippies meet the lawyer George Hanson, played by Jack Nicholson, who joins them and marvels at their freedom.

“Don’t ever tell anybody that they’re not free; cause then they’re gonna get real busy killin’ and maimin’ to prove to you that they are,” George warns them one night. Minutes later, he is bludgeoned to death in his sleep.

As we cross into Maine, we blast “No LSD Tonight” by Jeffrey Lewis. The myth of the psychedelic roadtrip is embodied by Ken Kesey, host of the first Grateful Dead gigs, who traveled from California to New York, giving away acid. The journey he made with his “Band of Merry Pranksters” was a fascinating attempt at a radical reversal of our violent westward expansion. However, it still accepts the fundamental argument of our American conditioning: Freedom is earned through exploration. I look out at the horizon of the highway, slicing open the soft savagery. It occurs to me that maybe I’m looking for love in the wrong place, desperate for pride in a country which offers up mostly ugliness. As we pull into the local brewery where the fan-meetup is held today, I feel anxious and uneasy. J-Mac is in a similar funk, so I decide to give him space, editing, writing, and exploring before it’s time for doors.

The sky is clear. The back of the lawn rolls off into the river, and cars zip past on the distant highway bridge. J-Mac sees two bootleggers he recognizes, Ben and George. They are all wearing each other’s shirts. Ben declares that tonight if they play “The Dripping Tap,” the band’s 16 minute opus from their 2022 record Omnium Gatherum, he’s gonna be the first one to crowdsurf.

Up front, a security guard pulls all the photographers aside and tells us the rules of the photo pit. His name is Dallas, and he wears an American flag hat atop his round, red face.

“Do you like catching crowd surfers,” J-Mac asks. Dallas grins ear to ear, revealing a chipped tooth. “I love it,” he chuckles.

During the middle of Geese’s set, Cameron stops unexpectedly. “We’d like to take a moment to wish our bass player Dominic a very happy 22nd birthday.” He holds his phone to the mic, and begins to play “22” by Taylor Swift. Soon, the synth table once again rolls onstage.

“We’re gonna try to play some techno for a little bit,” Joey says, announcing their arrival on stage.

Stu speaks next – “Look at where we are . . . this is beautiful.”

They open with several songs off The Silver Chord, including an almost 20 minute version of the title track. The air is electric as the 808 cowbells, claps, and growling bass create a deep trance.

When they wheel the table off, they launch straight into the thrasher “Gaia,” pulling the same trick from Boston. Joey even comments during a breakdown on “This Thing” that “tonight is just like last night in every way, but way sicker.”

They play the opening suite to Im In Your Mind Fuzz, the first album of theirs I ever heard. As I try and stick my camera high up enough over the tall stage, I am grinning like a little kid. I think of concerts I went to with my Dad in middle school: Tedeschi Trucks, Foo Fighters, Jack White . . . I thought nothing of weed or mushrooms or acid those days. All I knew was music. I feel a familiar high for the first time in years.

The band is riding their own high. After “Trapdoor,” Joey shouts, “We’ve tried a lot of new things together; some of them went well, some of them went crap, but overall . . . this is the best night of my fackin’ life!”

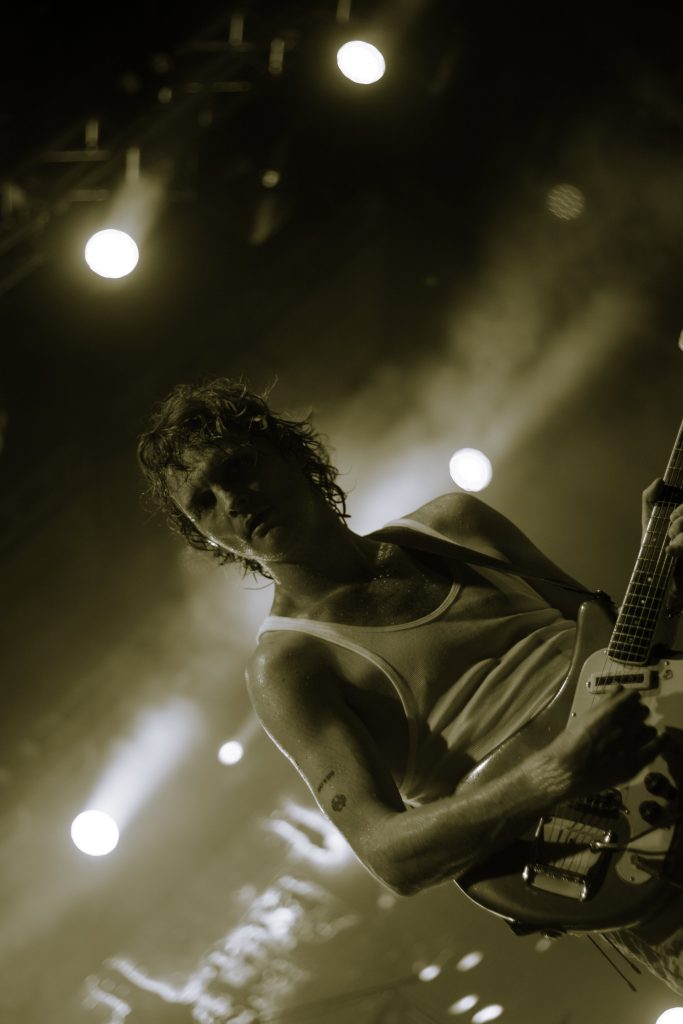

If the show ended here, it would still be one of my all time favorites. Churchlike organs start to rise. Ambrose climbs down on top of the massive subs in front of the stage. He belts out the opening stanzas of “The Dripping Tap.” Everyone screams along. Stu begins playing the main riff at breakneck speed. Ambrose shrieks, the drums build to a big fill, and I instinctively start to jump up and down as Ben’s lanky figure flys over the crowd.

After a several solos, the band teases, “I want to see you to take Stu away to that lake . . .” Stu grins. He begins to strip his shirt and socks. Security shoves us out of the way as we all stick our cameras up in the air.

“What’s gonna happen is, I’m gonna jump out, we’re gonna have a big group cuddle, and then we’re gonna go into that muddy as fuck body of water and do some weird shit,” Stu instructs the sea of people. He dives into the crowd while the band continues – “Drip, drip from the tap, don’t slip on the drip.” He floats all the way to the lake, flips off the spectators, and jumps into the water with a shirtless fan.

A few minutes later he is delivered back to the stage, wet and dirty. He picks his guitar back up, rips through the final chorus. Victorious, he declares, “We’re all gonna sleep good tonight!”

Maybe the band will, in the comfort of their tour bus. J-Mac and I, however, have to drive ten and a half hours to reach Toronto before tomorrow night. The long journey is the last thing on my mind as I wander aimlessly back to the van mumbling to myself.

When I meet J-Mac, he tells me that bootleg Ben and his friend Danny are down to convoy with us to Toronto. We plan to keep an eye on each other and make sure we all make it to Canada safely. While we fill up our cars at a nearby gas station, we all talk about the show. “This is something that we’ll tell our kids we were there for,” Ben says excitedly, and I honestly believe him. We grab some Red Bulls, agree on a route, and start the journey.

J-Mac insists that he has enough “personal demons” at the moment to keep him awake and alert, so I drive first. Ben and Danny were complete strangers to me hours ago, but tonight the sight of their white Subaru guides me down the road and puts me at peace. There is something ghostly about an empty highway.

We listen to the first Wu-Tang album as we retrace our steps from the weekend and drive through New Hampshire, Massachusetts, and into New York towards Albany. After a few hours, our convoy stops again to use the bathroom. J-Mac takes over and our comrades also trade shifts.

As we continue down the dark road, he plays music that reminds him of old girlfriends. He says that it helps him stay awake. I suspect he is looking for an excuse to wallow in it. I happen to enjoy wallowing. I ask what he wants.

“To be in love,” he says plainly. We sit in silence for a minute . . . I start to talk about it. I don’t tell very many people about it. Tonight, my words are not unkind. I tell him about love and loss and broken dreams of anarchy.

Trust me.

It was beautiful.

It was ugly.

It was music.

I write all of this at 3:38 a.m. as J-Mac silently smokes a cigarette through the cracked window of the van. Bonnie Raitt sings to us softly- “Thank you, baby, for giving me my life . . .”

The dark forest slips through the quiet concrete corridor of the American freeway.

A NORTH AMERICAN TRADITION

August 21st, 2024

TORONTO, ONTARIO

“Are you sure you don’t have any weed?” J-Mac asks. We are 30 minutes away from the Canadian border at Niagara Falls. “Not that I think you’re hiding anything . . . I just want to make sure,” he adds politely.

I am learning a lot about J-Mac on this trip already. Traveling in such close conditions has forced a brutal authenticity between us; all of our daily habits are on display. While I am growing slightly annoyed with his OCD and constant need for confirmation, his insistence on sober traveling is a comfort. We are doing nothing wrong and have nothing to hide. I double-check; there are no drugs in our van.

“Did you make sure that your passport is up to date and everything?” J-Mac asks next. My stomach sinks. I rummage through my backpack to find the little blue book – it expired back in January.

J-Mac is calm but . . . he’s definitely not happy. The worst they could do at the border is turn us away, so we decide to try our luck. We pull in line at the border check, and a hand pops out of the booth and waves us forward impatiently.

“Okay . . . we’re idiots, we don’t know anything,” J-Mac instructs me as we prepare our act. We hand over our passports to The Guard, who sports a bulletproof vest, black shades, and bald head.

“James, your passport is expired,” The Guard says stoically.

“Oh . . . really?” I say, stupid.

“Any drugs? Any guns? Where you going?” The Guard asks, unmoved by my performance.

“No drugs, no guns, following King Gizzard and The Lizard Wizard.”

“What kind of a band is that?” The Guard asks.

“Uh . . . it’s a metal band,” J-Mac responds grinning. We sit in our four-wheeled shrine to Jerry Garcia and wait anxiously.

“Ok . . . enjoy the concert,” The Guard tells us. We thank him. He doesn’t seem to care. J-Mac rolls up the window and we cackle as we finally cross the frontier.

On this trip, I have been trying to relate everything that happens to me back to a bohemian fantasy of American freedom. Driving down King’s Highway 405 to see an Australian band play in Canada . . . I realize that was a little bit silly of me.

J-Mac blasts hardcore punk and smokes cigarettes out the window while he cruises us into foreign territory. The excitement of making it into Canada is starting to fade when my phone rings…it’s Our Friends. We met Them yesterday before the Portland show as they sat in the open trunk of a van outside the venue. “Free Frame! For Sale! Freeeeee Frame, Fooooooor Sale!” One of Them had shouted at us in Portland, holding out a bright red mushroom sticker.

“The sticker’s free . . . the sale is on the back,” The Other One said, giggly.

I hold the phone for a long time as it shivers in my hand- “Uh, J-Mac . . . it’s those guys from Portland.”

“See what They want,” he answers nonchalantly, balancing a Camel Crush in between his lips. I answer the phone, nervously.

“Guess who made it into Canada!” One of Them cheers.

“The Guard took all of our Adderall and weed and fined us $1000 dollars,” The Other One chuckles, undefeated- “Lazy pig . . . he didn’t even look for all the acid!”

They start to bicker about whether or not they should take as many tabs as they can tonight or save it for the rest of tour . . . I hang up before I can ask the question that burns in the back of my throat. I look to my right and see the distant skyline of Toronto across Lake Ontario, and take a deep breath.

It sure is nice to be away from America.

The Band is really right in front of us tonight . . . Stu drops his water bottle cap and it falls at J-Mac’s feet. Stu beckons for him to hand it back. “Did you just see that!?” he runs up to me and asks- “Our fingers touched!”

For the first time on tour, the synth table closes out the show. The energy does not dip, but everyone has a second to breathe. A group of 4 or so people with VIP passes enter the photo pit with beers in hand; they crowd around Ambrose and start shouting friendly taunts at him. A cloud of smoke rises from between 2 of the massive subs nearby the party. I investigate. Someone is crouched down, not-so-secretly smoking a joint. He notices the hunger in my eyes: “You want a hit?” he asks.

After the show, my mind is moving fast. J-Mac and I walk into the emptying pit where Our Friends are waiting.

“Did you guys have a good night?” I ask Them.

“Bro . . . I just saw King Gizzard and the Lizard Wizard. It was a great night.” One of Them says. He looks at The Other One.

“Bro . . . where’d your shirt go?” he asks.

“I don’t even remember it coming off . . .” The Other One smiles distantly. His pupils are like big empty marbles.

MILK AND HONEY FOR MY BODY

August 21st, 2024

TORONTO, ONTARIO

The following are edited excerpts from a long conversation J-Mac and I had that night with our host in Toronto, Vic McNabb. J-Mac met her through Dead and Co. and she has become a prominent member of the King Gizzard fanbase as well. That night, we snacked on candy in her living room and talked about music, travel, and sobriety. Follow her on Instagram: @milknhoney4mybody

J-Mac: How did you discover King Gizzard?

Vic: I actually got tickets for Dead and Company, thinking it was a John Mayer show. I told my coworker about it. He started showing me the Dead, and he liked King Gizzard too. I saw Gizz for the first time at REBEL, a nightclub in Toronto, in 2019. That was the first mosh pit I had ever been in – I was wearing high heels. I was completely sober, but I felt the music take me over; I was hooked.

Jamie: How similar are the King Gizzard and Grateful Dead scenes?

V: I think Gizz has carved out their own niche. You can pin a Deadhead pretty easy. They’re a hippie who likes to do drugs . . . maybe they’re a nepo baby. Gizz is a little bit unique. There’s a growing number of women and queer people in the community, which I love. They’re very outspoken . . . that’s something I would criticize the Grateful Dead for. They never spoke out. Jerry was notoriously an “I just want to let people be” kind of guy. There’s almost a level of blindness in the Dead scene . . . but I wasn’t around in the Jerry days. I wish I was, but I’ve also heard a lot of horror stories about how weird it was to be a woman following the Dead.

J: What’s it like being a woman in such a male dominated scene?

V: There’s never been a show I’ve been to without having a weird interaction with a guy. I’ve gotten full ass-grabs in the pit. Gizz pulls in female and queer fans, but also metal fans . . . metal is very male-dominated. It is never be okay to grope someone in a pit, or punch someone so hard that it ruins the show for them. That weird stuff has been overlooked in the metal scene in the past. The Gizz fanbase kinda challenges that. I made a Facebook post about my experience as have other women. I think people are talking more and more about what we can do at shows to make sure that this shit is not an issue.

J: Do you think that the Gizz community is growing because Dead and Co. is no longer touring?

V: It’s definitely a growing community. Gizz talked about it recently in my friend Isabel [Glasgow]’s cover story for EXCLAIM. She asked them about their cult. They said it was something really unique to North America. There’s this younger generation of people who got into the Grateful Dead either through their parents or, if you’re like me, through John Mayer. You realize that this interesting culture of chasing music that you love is dying, but there’s something new: King Gizzard and The Lizard Wizard. They’re not Led Zeppelin, but there’s a subset in North America who are very eager to follow them. You might not find a ton of people who feel that way in your city . . . but they’re in your country. If you’re following shows you will meet them.

JM: What makes you want to chase live music so badly?

V: Its freeing. In the last few years I’ve been able to hold decent jobs, so I’m able to afford it. Every show is different, so you start to chase deep cuts. I’m a spinner too. I love dancing. When I started to explore sobriety, I realized that live music actually feels like it gets me high. When I’m in a Dead pit spinning for 10 minutes straight . . . it feels like I’m on shrooms. I walk out of a show, and I’m dancing on the way to the bathroom. Now that I’ve bitten the bullet on my sobriety, it’s something I really look forward to. It’s almost like chasing a new drug.

JM: How do you stay sober at shows?

V: One of my biggest motivators for staying sober is wanting to actually remember the show. If I stay sober, I know if I get anxious I can just move to side and then be okay. When I’m drinking or doing drugs and I get anxious, I don’t know where it’s coming from – is it the drugs, is it the fact that I’ve been diagnosed with anxiety, is someone creeping me out – I can’t distinguish it. I appreciate the clarity of sobriety. What about you?

JM: If I have a reason to be somewhere, then I’m okay. I love concerts. I used to go clubbing alot because that’s what I thought I had to do to have fun. I don’t like the music enough. Having people like Jamie who aren’t clean, but will hold me accountable helps . . . wearing my one show at a time sticker helps . . . volunteering at Wharf Rats meetings helps.

V: Four years is no joke. That’s awesome.

JM: Thank you.

ON THE BEACH

August 22nd, 2024

BETWEEN ELMDALE AND HOLIDAY HARBOR, ONTARIO

It is 11 p.m. by the time we make our way through the maze of white windmills; we pull into a pitch-black, industrious lot. “Damn . . . we’re really in the middle of nowhere,” J-Mac says. Neil Young hums through the car speakers.

We woke up in Toronto this morning at Vic’s apartment and spent most of the day driving back to Niagara Falls. We explored tourist traps on Clinton Hill and tossed coins into The Abyss before beginning the drive to our resting place: a parking lot on the Lake Eerie beach, about half an hour from the Detroit show tomorrow.

A distant lighthouse and a harbor filled with a few boats is to our right. We walk to the empty blackness of Lake Erie . . . I’m beginning to feel unwell.

I wake up early the next morning and walk to the beach. Breakfast today is a warm bottle of water and my burnt vape. When J-Mac joins me, we strip to our underwear and wade into the water. It cools my worries. We sit on a picnic bench and dry off; I notice an older man in motorcycle attire standing nearby smiling. A woman joins him, holding a lunch box.

“Can we share your table?” they ask politely.

They are Peter and Sue, a couple from Windsor who drove to the beach for the day on their motorcycles. They start to eat their snacks and ask us about our trip. We are 20 year old students in New York, and we are following the Australian psychedelic rock band King Gizzard and The Lizard Wizard on tour. They’ve never heard of that band before.

We learn that when they were young, they traveled all across America in a van. Sue moved back home after a breakup and got a job working in Peter’s store. They fell in love, fixed up an RV, and went off in search of their new American home. As it tends to do, America disappointed them, and they moved back to Canada. As they reminisce about their journeys, I realize that they found the belonging they were desperate for, not in the thrill of American adventure, but in the quiet comfort of each other. I tell them that they’ve lived a beautiful life.

“It came at a cost,” Peter tells us, “Our brothers and sisters worked while we traveled . . . we could have been much wealthier.

“But have fun and enjoy your youth,” Sue tells us. J-Mac quietly rips another hit off his Geek Bar. Sue continues looks out into the Eerie waters.

“Sometimes I still like to ride on the back of his motorcycle and hold my hands around him . . . just like when we were young.” A wave crashes onto the sand. The water rushes up to our feet and quickly retreats back home.

They are finished eating, then they are gone. J-Mac and I return to our beachfront baptism. The lake glimmers in the morning light.

THE TRUTH

August 23rd, 2024

DETROIT, MICHIGAN

I am blissfully ignorant of the fact that I look wild and stink of Lake Erie until we walk up to the register at Third Man Records. The girl behind the counter smiles warmly at me. “How can I help you?”

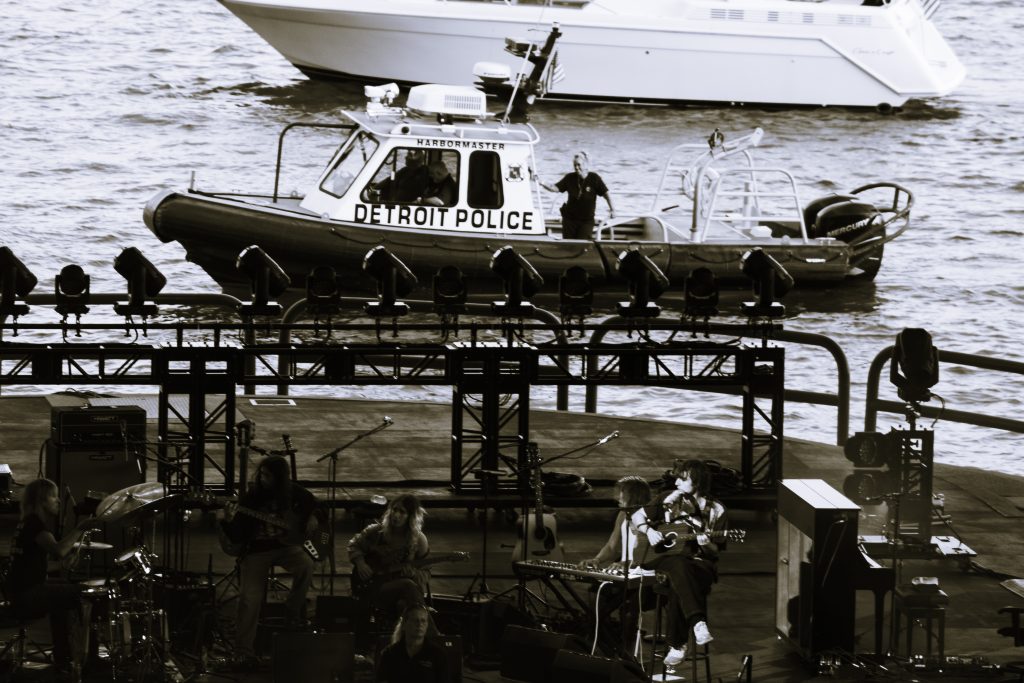

“What else should we check out in town?” J-Mac asks her enthusiastically. After a lazy morning on the beach, we drove back into America without any problems. Now, we have a few hours to kill before tonight’s acoustic set.

The Employee moves to the computer and lists a few other record stores before she looks up from the screen and pauses. “Have you guys been to the DIA yet?” she asks. We have not. She opens a drawer.

“We get complimentary tickets and . . . I think we’re allowed to give them out,” she says, raising one eyebrow. She hands us two tickets. Her name is Avalon.

We drive a few minutes and then park outside the Detroit Institute of Art. Inside, I am observing a huge oil painting of the Madonna with Child when J-Mac creeps up behind me. He whispers in my ear softly – “skibidi toilet . . .”

We are very similar in a lot of ways, but still very different people. It’s good to have friends like that, I think. We’ve been together 24/7 now and it has gone smoothly . . . at least as smoothly as you imagine. He’s a little fuck, but he’s a lovable little fuck.

After exploring the museum, we see Vic inside the Aretha Franklin Amphitheatre. She’s wearing a Butterfly 3000-inspired outfit, complete with wings. She is plotting to start a spinner section with her friend Mak tonight. We are only supposed to photograph the first three songs at this venue, and I am excited to relax and dance after a stressful few days.

During the show, I snap just a few pictures and quickly join J-Mac, Vic, and Mak, spinning in circles on the concrete. I understand what Vic meant; this is almost like a drug. The more I spin, the more it feels like the natural thing to be doing. Mak is smoking a joint next to me. He is dressed colorfully in tie dye pants, a tie dye shirt, a tie dye headband, and a tie dye robe. He offers a hit to Vic. She politely refuses; Mak turns to me next.

The Band begins to play one of my favorite songs, “Rattlesnake.” For the first time on tour, I feel the music take me somewhere else – spinning, spinning, spinning. I catch short glimpses of my two new friends. I am overwhelmed with music; heavy and dense. The Band plays “Fourth Colour.” Mak yells something unintelligible and sprints down to the front of the stage . . . after the euphoric peak of “Her and I,” he reappears, racing towards me – “YOOO!!!”

I hug him like he is my best friend coming home from war; I feel the sweat soaking through his tie dye. Our group begins to filter out. Without music, my mind dances me into a dizzy. We are crashing with my friend Bruno tonight. He lives an hour and a half away in Ann Arbor. It’s getting late. He was kind enough to host us at the last minute. We won’t get there until after midnight. We have to leave early to make it to Ohio. I won’t even get to talk to him. He’ll probably think I’m an asshole.

Mak is looking blankly back at the lawn where we were dancing.

“I hope my friend got those posters he left with me. . . they were really expensive . . . he bought a bunch of them for other people . . . I was supposed to grab them . . . I hope he got them.”

He looks back at me and smiles slowly.“Dude . . . I’m sohigh right now.”

BRUNO AND CAMILLA

August 23rd, 2024

ANN ARBOR, MICHIGAN

We park the van on a quiet street just past midnight. Someone walks up to the window. J-Mac rolls it down.

“Were you following me?” the man asks.

“No, we’re just parking.” J-Mac says.

“Oh, I thought you were following me,” he replies calmly. “Got any cash?”

“Sorry, I don’t,” J-Mac replies. “Want a cigarette?”

“Sure. Thank you,” he says. “Enjoy Ann Arbor.”

I’m collecting my things from the back of the van when I hear another voice from the street – “Jamie?” I turn and see Bruno walking towards us. I give him a big hug.

I met Bruno on one of the first days of my freshman year at the radio station. One time we were studying together in the library. I looked up from my laptop and there was a tear streaming silently down his face. I never acknowledged it. I kept talking about tape machines. I regret that.

I knew he had a girlfriend in Michigan. He had a tattoo of her name on his arm: “Camilla.” She would come visit him occasionally. One day I sat in the park by myself, and from a distance I saw the two of them sit on a bench and hold each other’s hands.

My heart broke that day the way it breaks as I walk into the studio apartment the couple now shares together in Ann Arbor. Bruno and I catch up for a few minutes. He is studying Music Education at the University of Michigan now. He teaches guitar to local kids. I ask him if he’s happy. He smiles. He is.

I wonder if I’m happy.

Bruno goes back to bed. J-Mac and I try to share the sectional couch. I wake just a few hours later. I don’t remember where I am. I drink some water and squeeze a bit more conversation in with Camilla and Bruno. They have to get to work . . . we have to get to a fan-meetup. Camilla makes us PB&J’s for the road.

I apologize. We didn’t get to hang out for very long. Bruno smiles warmly.

“I’m just glad I got to see you.”

CRUSH DYES

August 24th

CLEVELAND, OHIO

At the fan-meetup in Cleveland, our good friend, Clayton, walked over to J-Mac’s table to say hello. We asked him to give a quick interview on his experience following King Gizzard and selling tie-dyes, which he did with characteristic enthusiasm and kindness. Follow his work on instagram: @crush_dyes

Clayton: Tonight is gonna be my tenth Gizz show! I tie-dye shirts, and I’m doing the official tie-dyes for Geese. That would never have happened without Gizz. This community and this band has been everything to me . . . even meeting you guys. Y’all have been so cool. I have friends now from Canada to California. I never expected to be close to this many people.

Jamie: What do you think makes the community so tight-knit? Everyone we’ve met has been so genuine and kind.

C: The first thing that comes to mind is the music. The music brings us all together and we realize – “Oh, we have a lot in common.” But it’s not just the music, we’re all here for something.

J: What are you here for?

C: For you! For the people! I’m not gonna live forever! I want to have these experiences for as long as I can and make them meaningful.

J: How did you find out about Gizz in the first place?

C: My friend told me to listen to Infest the Rat’s Nest. It changed my life. I bought tickets that night to see them in Philadelphia in 2020 . . . guess what happened. My first show was Cleveland 2022. I went to Columbus and Pittsburgh too that year. They played “Float Along, Fill Your Lungs” to close out the Pittsburgh set. I bawled my fucking eyes out. I was thinking about the experience I just had. I realized that this is what I want to do. I never expected to get as involved as I am, but I wouldn’t want to be anywhere else.

J: I always used to think that this was a myth – all of these hippies following the band, meeting new people, seeing the country – I think it might be real.

C: It’s the American dream!

J: Well . . . it’s definitely a lot of fun. I feel like it’s a blessing.

C: Same, buddy. I’m privileged to be here. I know that for a fact. I try to take a minute at every show to look at everyone. We’re all there for one thing right in that moment, and it is so beautiful. I got heavy into the Dead right before COVID. I always wanted to follow a band, but the Dead is past my time. That’s why I started following Gizz . . . it’s historical. Our kids’ kids will know of King Gizzard, and we were there for it. This band has changed my life.

LIVE OUT

August 24th

CLEVELAND, OHIO

“You look like you’re doing homework right now,” a short girl with glasses and a cream colored King Gizzard shirt tells me. My laptop is in front of me dumping pictures onto my hard drive while I scrawl in my journal like a mad-man.

“Are you okay?” The Concerned Stranger asks. I laugh and assure her that I’m fine. I must look like death . . . I’m starting to feel like death too. We are at Brick and Barrell brewing, a local Cleveland Pub that is hosting today’s fan meetup. I decide to take a break from working and explore. I talk to several of the vendors. A woman is selling Gizzard baby onesies with her husband. I compliment them, and The Mother shows me pictures of her one-month-old back at home.

“Has the little guy has been to any Gizz shows yet?” I ask.

“We haven’t brought him yet because . . . we’re lowkey trying to trip,” The Mother laughs. “We will soon though,” she adds.

After the meetup, J-Mac and I head to the hotel that my Dad booked for us that night. After we check in, I immediately throw my belongings on the floor, strip to my underwear, and lay down on the first real bed I’ve seen since Boston. Determined not to move a muscle, I start to drift off into sleep. I am soon woken up by J-Mac – “We gotta go dude.”

I dress again; my wallet is no longer in my back pocket. I check underneath my bags and in my backpack – nothing. At this point, I am tired, hungry, and not thinking straight. I give up.

I am really in a bad mood as we enter the venue. Up front a short, bubbly photographer with pigtails hurries towards J-Mac and I.

“I want to be friends with all the other photographers!” they say. Their name is Sammy. Their enthusiasm makes me feel a little less angsty. They ask me why I’m here.

“I write for -” I begin, before The Photographer interrupts.

“Oh my God . . . pleeease say you write poetry! Oh my God . . . do you write poetry?”

The Band is having an off-night as well. Usually stage hands deliver shots periodically throughout the set. Tonight only water is passed around. After a brief journey into the moshpit and a conversation with an older man who has attended over 100 Mott The Hoople shows, the night is over.

In the parking lot, Our Friends are sitting in the back of their van, selling grilled cheese sandwiches for five bucks a piece.

“Free Frame! For Sale!” One of Them shouts out at the passing crowd.

“We’re gettin’ fucked up daily,” The Other One sings to himself as he flips a messy piece of bread on a hot plate. J-Mac and I sit on the concrete and chat with other hungry concertgoers. Someone laughs: “I wonder how I’m going to explain to the people at church where I’ve been.”

Coralie is a Mennonite and the director of her church choir. I ask her if she thinks that God was at the show tonight . . .

“Where charity and love are, God is there,” she quotes.

I start to think about my missing wallet. The money does not upset me. There was a flimsy, wooden guitar pick tucked in there. It displayed a small heart and the words, “Live Out” – a small memorial of a drunken admission – “I Love You.” That was two years ago now. J-Mac drives us back to the hotel; neither of us say a word.

I’m ready to go home.

ON LYGON STREET

August 24th

As I moped about my missing wallet before the Geese set in Cleveland, J-Mac caught up with our new friend Austin in the photo pit. We met in Boston and looked forward to talking to him in the photo-pit everynight. Follow his work on instagram: @onlygonstreet

J-Mac: Do I have a booger? Oh, we’re recording. Well, that’s going in the magazine. Tell us about yourself.

Austin: My name is Austin and I’m from Troy, New York. Tonight is my eighteenth King Gizzard show. The first thing I heard from King Gizzard was Im In Your Mind Fuzz. It’s a band name and an album name that really sticks with you. Years later, a friend showed me Quarters and from there I was fully hooked. I really saw their versatility as a band.

J: You’re shooting the show tonight. How did you start taking pictures of Gizz?

A: I got really into photography over quarantine. I was doing landscapes at local nature preserves. When I got into more music and starting going to local shows, I started bringing my camera. That was around the time I got really into Gizzard. When I saw my first show in Vegas, I learned just how free the fans were to do whatever they wanted. I was meeting people online, like Isabel (@hauntedyachtclub). She had recently shot their Toronto show with a photo pass. She told me how to get one, and I’ve shot 8 shows on this tour so far.

J: Do you prefer concert photography?

A: A lot of the photography I’m into stems from music. I was into classic rock growing up and I really loved Mick Rock. I still love older music photographers like Anton Corbijn, but a more journalistic approach is what I’m after. I’m so bad at structuring and composing a photo with people in it. When it’s just a bunch people doing shit already, I can try to make it into something cohesive. I like to show up and make it work. That’s what I’m about.

J: Why are you on tour?

A: It’s fun. I love the band and the unpredictability of the shows. I also love meeting so many people, not just in person. A bunch of people have seen the pictures I’ve taken of them at shows and reached out.

J: That’s how we met! You took a sick picture of me crowd surfing in D.C! What do you love about King Gizzard?

A: You never know what you’re gonna get, live or in the studio. It’s always unique. That and the amazing welcoming community.

NO LSD TONIGHT

August 25th

NEWPORT, KENTUCKY

“I want to do drugs tonight,” I declare confidently to Our Friends – I sound like a cop.

I checked my bank account earlier today to find $200 missing and various charges made at local Cleveland pubs. Losing my “Live Out” guitar pick has added insult to injury; I am beginning to feel very strange.

“I’m super down to give you a tab,” One of Them says to me. “I have a family member at the show tonight, so I’m a little worried . . .”

“Nah, nah, it’ll be discrete,” The Other One assures me. “Just come find us on the rail.”

“Hey man . . .” One of Them says to me. He smiles at me like he knows something I don’t – “. . . have a great night.”

I don’t have very long to consider the implications of dropping acid at a metal-adjacent psychedelic rock concert; excitement starts to bubble at the 16 Lots Southern Outpost, where today’s fan meetup is being held. A man with a big film camera is walking backwards through the bar. In front of him appear King Gizzard members Joey and Lucas.

The band members begin walking from table to table, saying hello and complimenting everyone’s creativity. Lucas comes up and talks to J-Mac and I for a few minutes. He seems genuinely interested in what we say. The energy is different than I would expect when a rockstar arrives at a meetup of their biggest fans; everyone is cool.

I walk towards the Ohio river, and my Dad calls me. He asks me if the tour has been worth it.

“I don’t know what I would be doing right now if it wasn’t this” is my answer.

“I do,” he says. “Sitting at your apartment alone, smoking pot . . .”

I’m not so sure I want to do drugs tonight. Slouched in summer sweat, I start thinking about the actual words that I have been mourning.

I was trying to say “I Love You.”

Instead, I said “Live Out.”

In Detroit, Vic told us, “I work to live, I don’t live to work.” The next day, I asked J-Mac which side he was on. He kept his eyes on the road and started grinning madly, “Dude . . . I just live!”

J-Mac joins me by the river. He just completely sold out of shirts and lighters. We watch the water together; it feels like I’ve never lived any other way.

“Do you feel free right now?” I ask.

“I want to do everything we’re doing: I want to get up early, I want to drive to a new city, I want to sell merch, I want to be at every show,” J-Mac assures me.

Inside the MegaCorp Pavilion, I see Our Friends on the rail.

“This is gonna be the sleeper set of the tour. I can feel it,” One of Them declares.

“Uh huh, uh huh,” The Other One nods enthusiastically.

Later, a kind woman at the front of the crowd grabs my attention.

“We’ve seen you every night!” she tells me. “We’ve been saying you look just like Stu’s little brother!”

Who do I think I am? I’m a poser. I don’t know this band well enough to be here. I’m not a photographer. Everyone knows it. They’re going to see me taking shitty pictures, and know what an asshole I am. These people paid to be here . . . I just walked right up to the front. What gives me the right? – Cameron’s dry wit interrupts my self-abuse as Geese takes the stage – “Hello Cincinnati area!”

By the time the opening set is finished the photo pit is packed. I am anxious and perpetually-in-the-way. Stu straps on his guitar and walks on stage.

“We’re gonna play some rock music tonight!” he shouts behind black sunglasses, jittery with energy.

I sure am glad that I didn’t drop acid in Kentucky!

HAUNTED YACHT CLUB

August 25th

NEWPORT, KENTUCKY

My nervousness grew throughout the night in Newport. I don’t remember much of the show . . . they played a really sick Nonagon Infinity suite . . . but I don’t remember much of it . . . while I unsuccessfully tried to keep my cool in between sets, J-Mac spoke with a Gizz fan whose name came up in our conversations with both Vic and Austin: Isabel. She interviewed Gizz for a great profile piece in EXCLAIM magazine and loyally shoots as many shows as she can attend. Follow her work on instagram: @hauntedyachtclub

Isabel: I started shooting King Gizzard the first time I saw them in Toronto in 2019. I shot them with my film point and shoot from the crowd. Toronto 2022 was my first time ever in the photo pit for any artist. I was really nervous. I had been shooting on film for about 8 years at that point, but I had never shot a concert on digital. That was such a positive experience. Nowadays, I like to split my time between the photo pit and the mosh pit.

J-Mac: You go to a lot of shows. What is it about Gizz that keeps you coming back?

I: There’s nothing I love in the world more than music. King Gizzard’s music is the epitome of everything I love. They’re incredible musicians, and I love watching them grow. They’ve opened so many doors for me and expanded my taste. Going to shows is my happy place, so I might as well be in my happy place a lot, you know?

J: I’ve always seen following a band as an American experience. It was something that started with Jack Kerouac, who influenced Jerry Garcia, who influenced thousands of Deadheads. Now I’m following an Australian band. You’re from Canada, and so is Vic. Do you think it’s an American experience?

I: Canada and America are way more similar than you would expect. A lot of people from Canada don’t follow the tour. It’s just me and a couple of friends. It definitely is more of an American thing, just because of logistics, like driving between the different states . . .

Crowd: GIZZ!!!

Stu: We’re gonna play some rock music tonight!

Later…

WHITER SHADE OF PALE

THOMPSON’S HOUSE

Across the street from the MegaCorp Pavillion, Thompson’s House waits; it’s faded facade follows me. Several columns stand guard in front of the colonial manor. Red brick rises, and through the concave black roof peers a small tower with a flat top. The sad silhouette looks down on me; I feel visible and vulnerable as we greet the House.

Inside a man sits behind a brown podium. He looks bored.

“We’re on the list,” J-Mac tells him.

“Sure enough you are,” The Bouncer says and chuckles to himself. “J-Mac and Jamie: the only two people on this damned list.”

J-Mac continues into the dark, unbothered . . . I hesitate. The Bouncer looks at me slyly – “There’s something you should know about this place…”

The beige wallpaper curls with age. Young boys in Union Blues cry out from paintings on the wall. Darkness grows longer with every step we make until we reach a dim staircase down; it softly swallows us. The belly of the beast is largely empty save for rock-and-roll instruments and a few thirty-somethings who lurk around the bar to our right.

“I don’t usually like going to the afterparty . . . people just come to get more fucked up.” J-Mac frowns, surveying the scene. I barely hear him; There is someone standing near the stage. A thin black veil covers her face, but she looks like . . .

“Do you see-” before I can call J-Mac’s attention to The Widow, a psychedelic swirl fills the room. Blues rock bubbles. Stage lights snarl. Rhythm runs away

I never untangled myself . . .

I thought I could vanish.

Still, I’m stuck.

J-Mac opens the door to the van. He’s wearing a tie-dye King Gizzard and The Lizard Wizard shirt, jean shorts, and Birkenstocks.

“All the moms in Marshall’s were staring at me,” he says. I am in a West Virginia parking lot in a puddle of my own sweat..

“I was just trying to pee . . . they were freaked out,” J-Mac continues. He takes a big sip from his water bottle and examines my condition. He starts to cackle wickedly – “We look like tweakers!

FREE FRAME! FOR SALE!

August 26th

HARRISBURG, PENNSYLVANIA

I have never felt like more of a loser and a poser in my entire life. I am laying down in the guest bedroom of J-Mac’s childhood home. This is the first true moment of reflection that I have had in over a week . . . something is upsetting me.

I wanted to use this trip to investigate the left-wing, countercultural remnants of this alleged “American experience” that J-Mac keeps referring to. There is one thing I have gotten very wrong: the hippies at the Human Be-In of 1967 were not the same hippies who followed Jerry in the 1980’s.

I think again of the dreamy vision I had when I first got in the van in Manhattan; I saw a copy of “On The Road” by Jack Kerouac on the floor of the van. I am embarrassed to admit that I hoped there would be a revolutionary quality to this trip. All this talk of “living free” made me feel like this countercultural fantasy I invented might actually be achievable. I was wrong; it was a story being sold to me. I bought in.

Once upon a time in San Francisco…

Mark Fisher outlines “the role that commodification [has] played in the production of culture throughout the twentieth century” in his essay Capitalist Realism. He describes “the establishment of alternative cultural zones, which endlessly repeat older gestures of rebellion as if for the first time,” ultimately dulling their radical potential. I think of the drugs and tie-dye and peace signs that I’ve seen this summer.

Fisher uses the tragic tale of Kurt Cobain to demonstrate this commodification. Quoting Frederic Jameson, he says that “Cobain found himself in ‘a world in which stylistic innovation is no longer possible, [and] all that is left is to imitate dead styles.” Cobain’s obsession with punk-rock made him outwardly aggressive towards anything mainstream, yet it is precisely this punk-rock attitude that attracted so much mainstream attention. In the end, Kurt Cobain became “just another piece of spectacle” – it killed him.

Right now, following a band on the road feels no more punk-rock than wearing a Nirvana shirt from Urban Outfitters. There’s nothing wrong with either of those things . . . but both represent images of youthful rebellion that have been flattened as commodities. There is nothing punk-rock about a commodity.

This “hero’s journey” of mine is just feeling more and more pretentious and privileged. I think most white suburban youths feel a certain longing for the “real” world – the one their parents, or school, or church have been hiding from them. This is in large part what attracted me to “do-the-whole-Kerouac-thing” in the first place.

In On The Road, Kerouac himself unflatteringly describes this inclination as “feeling that the best the white world had offered was not enough ecstasy . . . not enough life, joy, kicks, darkness, music, not enough night.” He admits, “I [wished] I were a Negro, [or] a Denver Mexican, or even a poor overworked Jap, anything but what I was so drearily, a ‘white man’ disillusioned.”

I recognize the similarity in my own thinking to Kerouac’s words, and it disturbs me. It was naive of me to think that I would be able to escape my narrow frame of reference.

What did I consider captivity? Suburban summers and a higher education in one of the most expensive cities in the world? I wanted to keep all the comforts of my privilege, and still be punk-rock.

Fisher’s critique is a commentary on this contradiction. The potential of alternative culture spaces for radical change is weakened by their inability to reckon with the violent power structures into which they are born. The reason that Ken Kesey’s San Francisco Acid Tests evolved, not into any measurable anti-capitalist action, but into $400 ticketed concerts at a tacky ball in Las Vegas is in large part because of the counterculture’s presupposed biases towards the dominant American systems.

Dr. Timothy Leary believed that psychedelic consciousness and an ambivalence towards structured politics might somehow wash us of our complicity in the violence that our society churns daily – “Turn on, tune in, drop out!”

I understand now that he was wrong. Still, this is not the Summer of Love . . . and King Gizzard and the Lizard Wizard are not The Grateful Dead.

The setting sun starts to creep through the blinds of the McKelvey family’s guest bedroom. I fall asleep, pen in hand.

Frusciante fiddles as Rome burns:

Climb the Heights,

Watch the Ashes Bury

Broken dreams of Anarchy.

A Wilting Flower sown in The Barrel of a Gun:

The floor of a van –

A man pulls up his pants –

Peace and Love and Violence worse than Death.

Woodstock 99’

Dedicated to Sammy.

DOOM CITY

August 27th

PHILADELPHIA, PENNSYLVANIA

These were my notes from Philadelphia:

- Benadryl – Short Drive to Philly – Sleepy – Philly Style Pizza with J-Mac’s friends Charlie and Hank – Owner Michael also went to NYU – “New York is not what it used to be,” too expensive – Walk to weed store and buy beer – J-Mac and Charlie goon -I drink beer, sleepy – miss Geese looking for parking, long line, odd venue – nitrous oxide tank – see J-Mac’s roommates, cut in line – walk to photo pit – ancy because not high – nitrous balloons – hang out after show with Austin and Charlie and Alex and Lily and Ava – Clout Bong, Charlie’s apartment, TAGABOW – would you rather more?

I didn’t mention King Gizzard and The Lizard Wizard once.

DIXIE CHICKEN

August 28th

RICHMOND, VIRGINIA

Notes:

- Wendy’s stop – miserable hot (103 degrees) – struggle to find parking – Geese set, sweaty – Cameron “does anyone have any bugspray they want to throw onto the stage?” – Carter, NYU Tisch alumn, made Gizz tour documentary Grow Wings and Fly – McKayla sees setlist and screams – Head On / Pill – Ambrose throws chicken out into the crowd – Anna, Ben, and Cole’s house – excellent hippie vibes – Dead tour stories – AI steelie art – hit bong, go non-verbal – bidet – find whippet on floor – Ween announces they are no longer touring – Shannon – I-85 South

LIVING THE WORK

August 30th

ASHEVILLE, NORTH CAROLINA

J-Mac and I were browsing Static Age Records and various thrift stores in the rocky hills of Asheville when he got the text message. We hurried over to the line that was forming for tonight’s show. There we met Guy Tyzack, a filmmaker travelling with the band on this tour. We climbed up a small hill to a quaint little church and sat in a circle underneath a statue of Jesus. His open arms overlooked the growing swarm of hair and colors outside the arena. Follow Guy’s work on Instagram: @guytyzack

J-Mac: I’ve seen you around a lot on this tour and you always have a camera. Can you talk about what you’re working on?

Guy: I don’t think it’s a big secret, but we’re making a documentary about the band and the tour. I’ll keep it as simple as that. We’re shooting on 16mm film. I did panic the other day and buy another digital camera and another tape camera. I just don’t want to miss anything

J: What is worth documenting about this band?

G: Years to come, it’s gonna be amazing to look back on everything. There’s no one like King Gizzard. They do everything that everyone says not to. It inspires people to get out there and make things. People can overcook and overthink things. Sometimes they won’t even attempt things. They think it’s gonna be crappy. It’s kind of sad. King Gizzard puts stuff out all the time and allows it not to be perfect. It’s created this rich creative space for everyone to be in.

J: Is this your first time on tour?

G: Yeah it is. It’s . . . good. It’s been slightly overwhelming. I’ve never been to the States before. It’s a new place, a new day, all the time. We’re halfway done now which is . . . yeah, sort of a relief. I know I’ll regret not going at it as hard as I can though. You’ve got to be working all day but you’ve got to get some sleep when you can. It’s pretty disorientating.

J: Jamie asked me on the first day of tour why I love being on the road. When I followed the Dead it felt like I was upholding this great American tradition. On this tour we’ve met a lot of Canadians. You and the band are all Australian. Do you think it’s still fair to call it an American tradition?

G: I think it is an American thing. We don’t have as many big cities in Australia. Plus, I think Americans get really amped on stuff a lot more than everybody else. They know what they love, and they go at it one hundred percent. In Australia the TV is always saying that America is on fire. Being here and meeting all these lovely people . . . the world feels a lot nicer than you think it is sometimes.

J: What do you love about documentary filmmaking?

G: I love meeting new people. I love outliers and outsiders – people who live life differently. I’m trying to discover these people’s perspectives. I read On The Road and was obsessed with that kind of lifestyle. Now I’m able to travel around, experiment with a camera, and meet new people. I’m trying to live like that forever. I’d be really depressed at a 9-5.

J: What advice can you offer to young creatives who are trying to capture scenes like this?

G: Don’t force your own perspective into the people you meet or interview. When you’re editing it all together, try it out in various ways. It’s a puzzle that can put together really differently. If you find your own voice in doing that, it’s really cool. That can take years to create . . . I’m 33 now. Creativity is generally about being really consistent and not giving up. Just keep doing it.

HER AND I

August 30th

ASHEVILLE, NORTH CAROLINA

After talking with Guy, we made our way down the hill and started talking to people in line. We knew that this was our last chance to get interviews, so we wanted to make it count. We heard that a couple had just gotten married in line for the show – a ring bearer, a walk down the aisle, everything. We spotted a man wearing a white dress shirt with cut off sleeves, a black vest, and a black tophat. “That’s our groom.” The following is our conversation with Gina and Jared, a couple from Charlotte, North Carolina . . . my parents met there in the nineties.

Gina: We got engaged at the Caverns last year. It was late in the night . . . I feel like you should be telling this story

Jared: I knew I wanted to propose to her during “Her and I.” The acoustic night at the Caverns was the best shot I had. That was the first night I brought the ring. There was a rain delay; the band was fifteen minutes over curfew by the end of the night. I figured it wasn’t gonna happen. We were leaving when I heard them tune to the key of “Her and I.” I started acting really weird – everything I was gonna say slipped out of my mind.

Jamie: How did y’all meet each other?

Jared: We worked at Mellow Mushroom together for almost seven years. We’ve been dating for eight years. We knew we were going to get married, and we were joking about doing a line wedding with our Gizz family. We were in Queens when we actually decided to do it. That was like . . . ten days ago.

Jamie: How did the wedding go?

Jared: It was raining, and the pizza was getting delivered. I’m trying to unload the van, when someone pats me on the back – “Are you the one getting married?” I can’t do the accent, but it was Cavs . . . I mean that’s just so cool. I would not have expected that. The band needs all the time off that they can get. It just says so much about Cavs, the band, and the whole Gizz team.

Gina: That’s another reason we’re so into Gizz. They’re just good guys.

J-Mac: How many Gizz shows have you been to?

Jared and Gina: 33.

J-Mac: Oh my God! You guys have been to every show together?

Jared: And we will forever. We’ll get to 100 one day.

Gina: We didn’t go to shows together for a while. He was really into Umphrees McGee. He would wait in line all day. I did not understand it at all. Then we both got really into Gizz. Now it’s our thing.

Jared: There’s so many people we would never have met and things we never would have pushed ourselves to do. This is all we do. We save up and wait for Gizz tour. We didn’t eat out for a year. We started rolling our own cigs, you know.

J-Mac: What makes you want to chase the music so badly?

Jared: Every single time I’m able to make a connection with someone here. People have been following bands for a long time, but I’ve never had this kind of family before. We have friends from Australia, Russia, the UK, South Korea, Vietnam . . . and now y’all.

Thanks for talking to us. Someone else said this already, but you guys have really beautiful smiles.

J-Mac: Thanks! We’re just happy to be here.

THE RIVER

August 30th

ASHEVILLE, NORTH CAROLINA

A strange feeling washed over me as we scurried up and down the line talking to friends, old and new. I knew I wouldn’t see these people again in a long time. J-Mac and I sat down on the concrete with Ben and Danny. The night that we convoyed to Canada together, they were complete strangers. Now we say goodbye. Follow them on instagram: @benbacon.exe and @boogiemandan_

Ben: My name is Ben Bacon. I think this is my 28th Gizz show.

Danny: My name is Boogieman Dan. This might be 34 or 35 for me.

J-Mac: Why do you guys go to so many Gizz shows?

B: I always felt like a loser growing up. People would make me feel that way. When I’m at a Gizz show I can be myself. I feel at home.

J-Mac That’s the story of my life dude.

Jamie: You and Danny have been inseparable on this tour. How did you meet each other?

Ben: Last tour, I was at a campsite with this guy named Drew. He got a text inviting us to a trailer party. It took us thirty minutes to find the pinned location . . . I was a little high. We show up and there’s this guy named Larry. He was wearing a clown nose and kept trying to give us beers . . . I took maybe one sip of that beer. Danny was there. He kind of followed us back to our campsite that night.

Danny: Woah not like that! I just wanted to leave the trailer … You said you had a Nintendo.

Ben: I found Danny after the next concert and I told him that it meant so much to me to find him. I just wanted to follow in Danny’s footsteps. He’s a really smart guy, he’s been to a lot of concerts, he knows how to go to these concerts. I wanted to learn from him.

Danny: I love you, bro.

Ben: I love you too.

Danny: For life.

Ben: Time went real quick, and now we’re twelve shows deep on this tour together. He hasn’t annoyed me yet.

J-Mac: That’s impressive. Jamie and I . . . there’s been a few moments.

Danny: I’ve got nothing to complain about. We’re on Gizz tour.

Ben: I went on tour with zero dollars to my name, and two maxed credit cards. Now I’m here. I have enough money to cover rent which is due tomorrow. I have enough money to get to the next show. I have enough money to feed myself. I’m proud of myself.

J-Mac: I’m proud of you too. I’m so grateful for this community.

Ben: I want this to be my life. I want King Gizzard and The Lizard Wizard to be my future. There’s more to life than getting a degree, getting a job, and having kids. I keep listening to the King Gizzard song “The River.” It lets me know that this is really possible, if I put my passion into it.

Jamie: Do you feel any judgement for not wanting the traditional white-picket fence life?

Ben: So many people in my life tell me that this is stupid. Everytime I hear that it hurts. There was this girl back home who I felt like I was in love with. I had to tell her that I couldn’t be with her. I had to follow my dream. It took me a while to find it, but what a beautiful feeling it is to have a dream.

Danny: I’m gonna miss you boys. Y’all are some cool ass dudes. I’m glad we met. We drove off into the middle of the night into Canada together.

Ben: It felt like we were Jedi Masters and you were our Padawans. We were showing you the ways of King Gizzard tour. Now that y’all are here it doesn’t feel like that at all. We’re totally equals. I’m not above anyone else.

THE BIG PICTURE

August 30th

ASHEVILLE, NORTH CAROLINA

J-Mac and I laid on the grass and waited for doors to open. We watched the long line of people from a small grassy hill next to the church. I turned to J-Mac: “Can I interview you?” Follow him on Instagram: @jmackmckelvey

Jamie: What made you want to follow King Gizzard

J-Mac: I went into this tour blind. I had met a few people from other communities I’m in that fucking love going to Gizz shows. I didn’t know what the vending scene was like. I’d followed Dead and Co before, but I already had hit local shows so I knew the scene. Dead and Co didn’t go on tour this summer and I wanted to be on the road. Billy strings wasn’t doing a big tour. I don’t really like Phish all that much. I really like King Gizzard’s music, especially the live stuff.

Jamie: What’s your big picture takeaway from the last two weeks?

J-Mac: I can really do whatever I want with my life. I made enough money off of shirts to pay for the entire trip and then go home and pay off some money that I owed and then still have a little bit leftover. I could’ve made twice as many shirts as I did and been able to cover rent. I really wanna stay on the road following bands or playing music. I love being on the road. I never want to stop.

Jamie: What do you want from life?

J-Mac: I want to feel good, I guess. Make art, meet cool people, go to cool places, share that art. The point of my life is . . . music. Yeah, it’s music.

Jamie: It’s always been music for me too. This tour has reminded me that I love music for it’s humanity. I’ve had nothing but positive interactions with people who trucked it from all across the country just for this one thing. It’s fully by humans, for humans, and with humans. I feel very . . . comfortable in my own skin in a way that I haven’t in a long time. I’m very at peace with being alive and going through it.

I’ve been seeing a lot of kids around… I remember seeing Foo Fighters with my dad and being like wow that’s Dave Grohl this is real this exists outside of the internet. That’s how I feel now looking at all these people in line. That’s my attempt at a big picture takeaway in this moment. Just the people, man. Look at em’ go.

J-Mac: It’s kinda cool that we’re ending it like this: watching all these people in line, listening to the church bells ringing.

EVERYTHING PUT TOGETHER FALLS APART

August 31st

GREENVILLE, SOUTH CAROLINA

I remember Asheville in small fragments. My friend Aidan was there. Catie’s brother Brady was there. J-Mac talked to @phishonphilm in the photo pit. I talked to Our Friends on the rail.

“I don’t know dude, weed makes me kind of quiet,” One of Them said.