The last time Black Country, New Road played the 575-capacity Bowery Ballroom in September of 2022, the entire setlist consisted of newly written unreleased material (bar a cover of Billie Eilish’s “Happier Than Ever,”). Seven months prior, the outfit had announced the departure of their frontman Isaac Wood, who held writing duties for the first two BC,NR records. The band, opting not to perform any of Isaac’s material without his presence, quickly assembled a new repertoire and took to the road to recover from the staggering blow their nascent stardom just took.

Nearly three years later, Black Country, New Road are at the Bowery Ballroom, once again, for a quick warm-up before they embark on tour for their first record as a reformed ensemble.

In the time between Ants From Up There, the band’s final effort with their former frontman, and the brand new Forever Howlong, Black Country, New Road’s celebrity grew virally thanks to a set of auspicious circumstances. Ants From Up There performed impressively for the little follow-up promotion the band was able to offer the record. An outsized online fandom gave life to unreleased material. A breakneck touring schedule offered new fans two or three opportunities to see the band during their recovery period. In two years, the band graduated from the sub-thousand club circuit to opening arenas and headlining festivals.

Forever Howlong illustrates Black Country, New Road’s rigamarole in the years before its release. Fine tuned compositions performed with the coherence of a metropolitan symphony orchestra are the foundation of Forever Howlong, while the band’s impish personality fills out the structure. Whereas the band’s first two records found life through a disorderly I-won’t-do-what-I’m-told punk attitude, Forever Howlong exhibits a band artistically matured through the fire and flames of its personal realities.

At the Bowery Ballroom, the band performed a clean runthrough of the new record, only dipping into previous material during an abridged version of “Turbine/Pigs.” When the ensemble broke out a collection of recorders to perform the titular “Forever Howlong,” the band’s silliness was superseded by their virtuosity with the instrument, both individually and as an ensemble. There was little room from improvisation, extension, or selection. The evening was a finished product refined by a lengthy process of trial by fire presented with utmost confidence. The night underlined a key factor of Black Country, New Road’s continuing success against the odds. Whereas bands of the past have allowed strenuous touring schedules, members departures, and quickly scaled fame to detriment goodwill and creativity, Black Country, New Road relish in their ability to find both imagination and discipline within lived experiences.

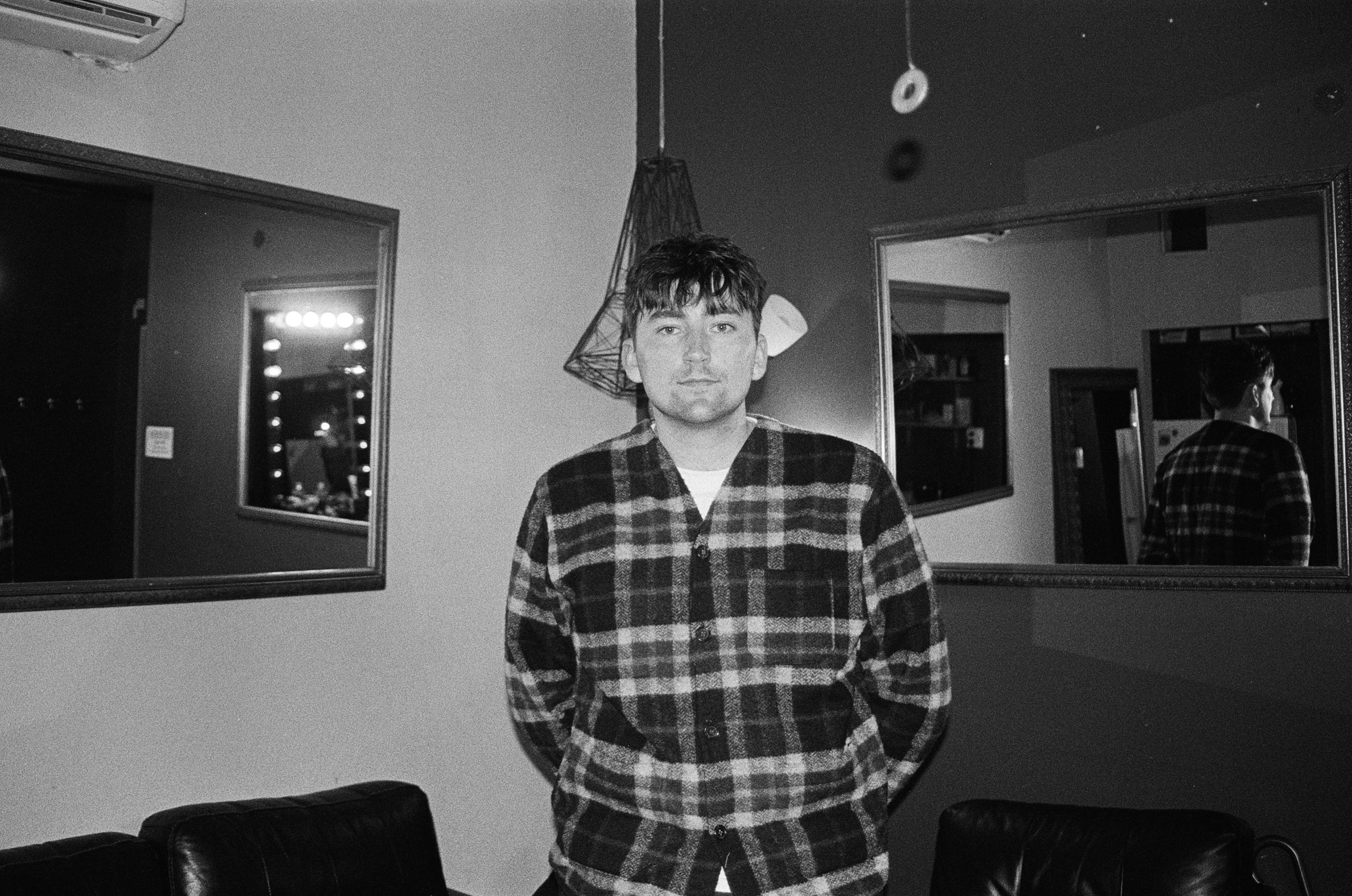

Ahead of their first night at the Ballroom, we sat down with vocalist, flutist, and saxophonist Lewis Evans to discuss pop stars, jazz education, confidence in arenas, and anxiety in clubs.

[This interview has been edited and condensed for clarity.]

People ask you a lot about the influence of artists like The Band or Joanna Newsom and stuff in that realm, but what do you learn from big budget pop music, from writing, recording, or the performance process?

It’s easy to say that, nowadays, all pop music is saturated and boring, and there is a lot of crap pop music, but there has always been a lot of crap pop music. I think we definitely look at it now with a rose tinted filter, like the old crap pop music. People who were into cool music found that music really crap at the time. There’s that, you should never feel guilty for liking certain pop music. But also, when it’s good, it can have a really scientific way of making you feel the emotion that the artist wants to make you feel, and also pop music tends to never beat around the bush. You can learn a lot from clinical it is, and obviously clinical music isn’t always the best music, but it can help you make your music a bit more straight to the point.

Coming from a classical education, just from personal experience, I know it can be hard to reckon those two worlds. When you were first getting your music education, was it difficult to even enjoy that kind of music with so much of this repertoire being taught at you?

It’s interesting. I had a bit of a different style of classical upbringing. I learnt classical music and I played a lot of classical repertoire, but I also was doing CAT (Centers for Advanced Teaching) schemes in the UK in the arts. They used to do them government funded, but I think since our Tory government, I don’t think they do that as much anymore. They were basically places for young people. They would audition and when they got in, you basically got taught from loads of people from different types of backgrounds. By the time I was 18- I think I started when I was about 12- I’d played with Cuban musicians, Nigerian musicians, played Afro-beat stuff, played with Jewish klezmer musicians, played with Brazilian contemporary folk artists. All kinds of different stuff. I was exposed to so much and my access to alternative music from this classical background, I was more excited about what I could put into it that had come from this melting pot of things I had learnt. I reckon if I had less of a diverse background I would feel much more intimidated by the prospect of working in this alternative music world, because it can make you a really stiff musician if you’re not careful. I think I was lucky, really lucky, to be able to see loads and play loads of different kinds of music.

You mentioned the clinicalness of pop music and I think that also goes hand in hand with how, especially from the 70’s to the 90’s, how big it was, like how maximal. When I listen back to Steely Dan records or Cheap Trick records, like they are just these massive walls of sound. That’s something I observe in almost all of the Black Country, New Road records, no matter which era. Are you interested in filling out as much space as you can, as a band or even as a performer?

It’s interesting. I feel like on this record, we tried not to do that, but we probably ended up doing that because of the amount of us and the kind of sounds we went for. Personally, on this record, as a sax player, and as the part that I play in Black Country, New Road, I really tried to take a back seat melodically. I’m usually countermelodies, that’s mainly my thing, and I can be quite busy with them sometimes, but on this record I really tried to not be too busy and only be embellishing in moments where I really needed to be, or where there was space for me to do so, because I wanted to allow the songs to really sit and sing for themselves. Some of the songs were really strong when they came into the practice room, before we’d even done anything with them. It meant that if I went too maximal with my own parts, then it wouldn’t suit the songs and it would be getting in the way of the girls, so I didn’t wanna do that.

That thinking makes me think of a lot of the great Miles Davis record, especially from his early fusion records where he’s pretty scant and letting his band take focus. Is jazz something you draw a lot from when you’re thinking about these compositions, especially in relation to this large ensemble?

I studied jazz at uni and, yeah, it was. When I started playing jazz at uni, I quickly decided I didn’t want to be a jazz musician. The way that jazz music is taught and the way young people often play jazz, or at least people in London do, is that it’s a chance to really show off. That’s fine, but it wasn’t really what I was into. I found the idea of playing a lot less much cooler. That is not to say I’ve been sparse with my playing in the past, because I listen back to old music of ours, very occasionally, and I always am cringed by how much I played. I wish I played less. The Miles Davis attitude, the notes you don’t play, that is really something I try to do. I love it on records where you can hear that they’re only playing when they need to play. The hard bop era stuff, I love the attitude to it. I really like the attitude to it. It’s not necessarily my favorite music, but I really like the attitude.

That’s interesting you say that about English jazz musicians, because I have a lot of friends who are doing jazz studies, and they’re really standards heavy. I have friends who can really emulate the free jazz spirit and they are getting hammered down by the jazz studies thing.

I got hammered down by it. They were, similarly, really language. Bebop language, bebop language, bebop language. I just didn’t really want to learn it. I thought at the time I was being lazy, but I look back on it and I was actually just not inspired by it. It’s not to say it’s not a good thing to learn, because being able to play with really nice bebop language sounds fucking sick. It’s just not really what I wanted to do. Jazz in the UK is probably quite similar, it’s very standards driven.

In an ensemble as big as Black Country, New Road, especially in the new material, the use of space feels very calculated. Just last week, I saw a performance of Terry Riley’s In C and there were about a dozen performers and I was really fascinated by the way each of them played for maybe just a few seconds to get their point across then faded out. I would imagine that amongst the band, it’s a primary challenge to ensure balance. What experiences or influences do you draw on when it comes to the use of space?

Good question. I think we definitely drew on bands that sound like fucking good bands, things like The Band. There’s this Fotheringay tune called “The Ballad of Ned Kelly” where they just sound so good and what sounds so good about it is the groove. When different instruments come in, it’s so effective because they’re not playing all the time. It’s the same with The Band as well, they just know when to play and when not to play. You leaving space for something else makes your entry then much more effective. I guess maybe that is the only music that we’ve been inspired by to have space, but it is just something we think about so much, and we really comb over the arrangements. Making sure everything needs to be there if it is there. Nothing is safe. You play these arrangements for weeks and weeks and weeks and maybe even tour them for two years, and then we’re like, “Actually, that whole thing that you’ve been there for ages doesn’t need to be there, it sounds better without it.” We don’t really look to certain things for inspiration on space, I think we just make sure that everything’s needed.

You spoke about this earlier, but the earliest BCNR material feels a lot more frenzied and angular. There’s a fascinating use of space there, in very different ways, but what do you credit to that attitude changing?

Growing up for sure. We were like angsty, thought we were really cool, trendy, but not very trendy, but we thought we were cool as fuck. You then make this frantic abrasive sounding music because it feels like the right thing to do at the time. Now, that’s not really the kind of music we’re into, so we don’t make that kind of music anymore. Definitely, on a personal level, my own player was so much bravado back in the day. Way more show-y off, like look at me, kind of thing, which I really try and veer away from now. It’s not really the kind of person I am anymore. It’s not like I wasn’t a nice guy back then, but I really wanted to make sure that my stake was in the game. That is definitely growing up.

When it comes to the arrangements, is that often something that is slowly developed or something that can change stage to stage, studio to studio?

It actually really depends. It depends on the song because there’s some songs where the arrangement just comes in straight away, like oh that’s great. I think “The Big Spin” on the new record probably only took four rehearsals to get the bulk of the song. We had this problem with the ending and we had this whole new section at the end that we were trying for so long, and it didn’t work. We were like, “Maybe let’s just not do that ending and let’s do something more simple,” and the simple ending won. That whole thing came together really quick, but then “For the Cold Country,” that is an example of a tune that took ages to work out. We were doing different versions of that on tours for a year-and-a-half, trying it in sound check. No one was really satisfied with it until we had to work something out. The song “Two Horses” as well, we had this really grandiose, flamboyant version of it, or at least the first half, that we were playing. It was just too much, and when we moved into pre-production, before we went to the studio, we were like, “This is actually worse than the original demo that Georgia made.” We just went back to that and did it exactly the same. It really depends from song to song. Sometimes they’re fully formed really quickly. Just depends on the kind of song it is.

Was it a little more comforting having more time to figure those things out for this record than the live album?

Yeah, it was so nice. That felt really rushed, and even if you’re happy with the songs, I’ll never feel satisfied by that, which is the reason we made it a live record and not a studio release. We didn’t have enough time to make sure we were 100% happy with everything. There’s so many things I would change on that, so many references and melodic moments, harmonic moments. Just stuff I would get rid of completely. We were going through the process of trying to play those songs again, and we gutted so much of it, stuff that we feel more comfortable doing now. It was really nice to have the time because it just means that we’re now playing music live that we’re really, really proud with every moment.

Almost three years ago, I saw you guys here at the Bowery Ballroom. A year-and-a-half later, I saw you guys at the Brooklyn Paramount, which is a venue that’s 5-times bigger. Those tours progressively expanded as they went on. Did playing those different sized stages and spaces affect the creative process as you noticed these crowds getting bigger?

I don’t know if it affected the creative process. It definitely made us feel more excited about how many people were gonna potentially hear the new record. It made us think about these songs are gonna feel to play live. Not necessarily thinking about crowd reaction, but thinking about like, “We might be playing this at some big venues, so we need to do certain things with the music.”

If anything, it made me feel so much more confident. We’d been shown so much love from people and so many people were willing to buy into what we were doing purely from unreleased music or a live album. We were really lucky to have so many people on board. That made us feel like we could feel confident in our own decisions and musicianship. It was just really helpful.

It’s like the Nicki Minaj line. “50k for a verse, no album out.”

Yeah haha, yeah.

I’m thrilled to see your show tonight because of how tight it’ll feel. What was the idea behind playing a show here before you launch back into it?

Um, I don’t….actually know. We just really love this venue. It was a bit of a last minute thing. We’ve been in New York to do a lot of press and we thought we should do a show as well. There’s no better venue in the city to play than Bowery Ballroom. It’s an amazing place. It sounds so good on stage. It’s the perfect sized venue. It’s amazing being able to play huge venues, but it never feels better playing anywhere from 50-600 cap rooms, like here. It never feels better than this.

Coming from the background of the 50 cap room, do you feel different pressures when you present yourself to 50, 500, 2500 caps?

They’re different, they’re really different. I feel pressure playing to 50 cap audiences because you can see everyone. Everyone’s so close and everyone’s so intimate. Then, when you play these 2500 capacity rooms, it’s guaranteed that some people aren’t going to like the show, and that’s scary. It doesn’t matter how many times people say “It’s fine, not everyone’s going to like you, you can’t please everyone.” That sucks. That sucks that you can’t please everyone. You want to be able to please everyone. When you play those bigger venues, ticket prices play more expensive. That’s more people who are there to see you perform. It feels like more pressure because you want to make sure everyone has the best time possible. It’s definitely more pressure in the bigger venues.

When it does get bigger, when it gets way bigger, it starts becoming less personal, and you can actually switch off the crowd almost, because you have way more space between you and the crowd. We played a support tour (for Nick Cave and the Bad Seeds) in arenas and it was so impersonal. That was also because it was a support tour.

Just to leave us off, do you have a nightmare story from when you were playing to the 50 crowds?

Oh loads. I’ve got a few really good ones. There was a period of time where my saxophone had broken- actually, the time when I broke my saxophone, we were in such a punky situation. I move head up and it just snapped the whole sax and my tooth. It snapped the crook of my saxophone. I had to get a courtesy saxophone, like you would get a car from a dealership, for about two months while they replaced this part. The saxophone, for some reason, when I played it really hard, made me gag. I used to have to play, then go off stage, and almost throw up. I would start to drink loads of whiskey when I was playing so that my throat was numbed. That was a pretty rough period.

There was also a gig that we played at a cricket club pavilion. This is not something an American mind will know anything about, but it’s essentially the most tinpot place you could play a gig in. It was in a shit little town somewhere in Bedfordshire, which is so far away from the Big Smoke. The only people in the crowd were Isaac’s girlfriend at the time and my dad. This DJ was on after us and he kept coming on the stage. My dad got really annoyed at him, and my dad’s very meek, a very sweet man. But when he knows something’s wrong he’ll tell them. This guy then came back on stage, he was called Big Dave, and he kept adjusting his DJ setup or something. We were really sweaty and he did it again, so when he came off, I went and got his headphones and I rubbed them around my sweaty head, and he was like “Nooooo!”