For psych-revival trailblazer Ty Segall, sometimes all a song needs to be about is how much he loves his dogs. “Go adopt a dog!” Segall says before the “dog portion of the night” in which he performed a collection of songs about his two pets to his Brooklyn audience. This seems like a common theme with Segall, with everything from his Goodbye Bread album cover to the original paintings he occasionally sells at his shows. Behind his vast discography and reputation as a juggernaut in his field, he’s just a guy who loves his furry friends.

Ty Segall is a creative powerhouse that shows no signs of stopping. Since 2008, he’s released 15 albums, not including live albums or releases with his several side projects. He released two distinct projects last year, first the beautifully dissonant and complex Three Bells, followed by Love Rudiments, an instrumental solo drum record. This year, he’s already debuted a new band, Freckle and their eponymous folk rock record, while Segall’s 16th solo effort, Possession, follows.

On Possession, Segall continues his drift away from the ear piercing feedback and fuzz of his origins. The record features lush string and horn arrangements intertwined into his familiar garage rock sound. The droning chords on album opener “Shoplifter” are contrasted by the lilting string melodies, reminiscent of orchestration on classic 60s psych rock records like Sgt. Peppers. Segall has noticeably improved his singing ability and songwriting across his past 15 albums, with songs like “Possession” and “The Big Day” featuring his catchiest vocal lines and guitar riffs to date.

Though almost every instrument on Possession was played by Segall in his home studio, Harmonizer Studios, the lyrics were co-written by his collaborator, filmmaker Matt Yoka. The narratives in each song are intriguing and mysterious. According to Segall, the 10 songs are a spanning anthology of American stories. “Possession” is about the Salem witch trials in the 1600s, while “Alive” is about the famed Donner Party cannibals. While the subject matters are bleak, this batch is, sonically, much lighter than 2024’s “Three Bells”. Dissonance has been traded for harmony, although that’s nothing new for Segall. While earlier albums like 2010’s Melted used sheer volume to fill the room, Segall is making his presence known on Possession with larger, sophisticated arrangements and carefully crafted songwriting.

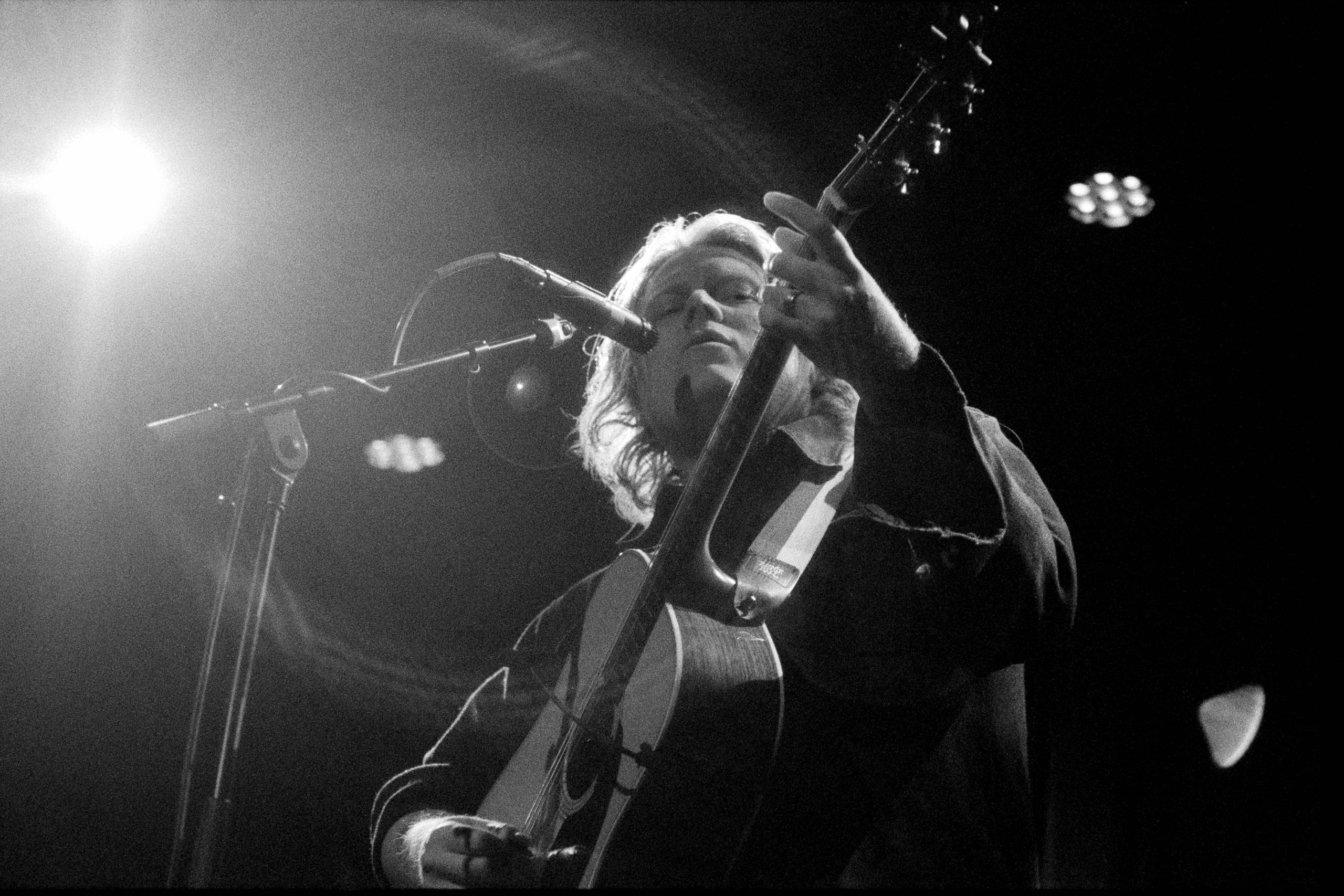

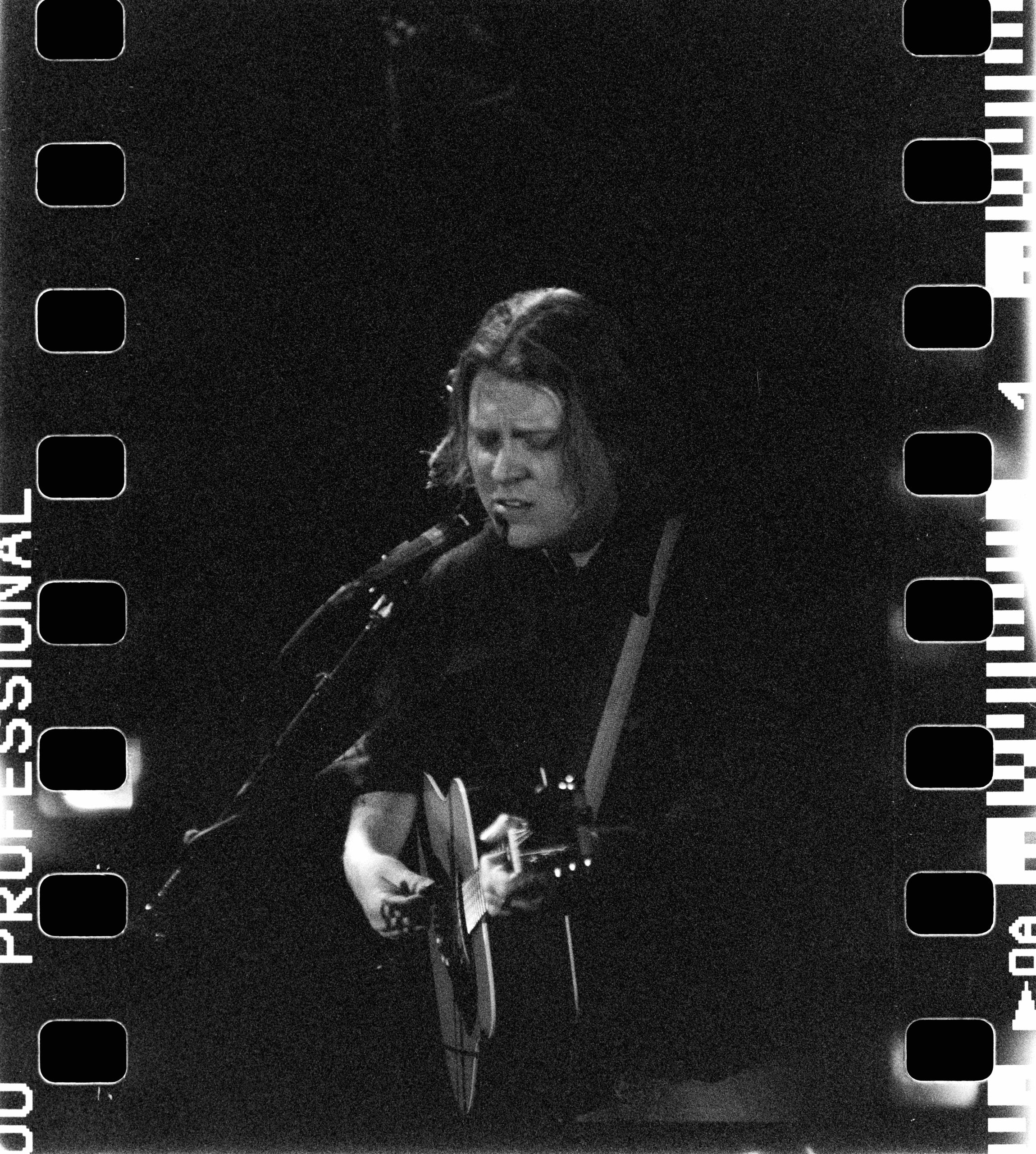

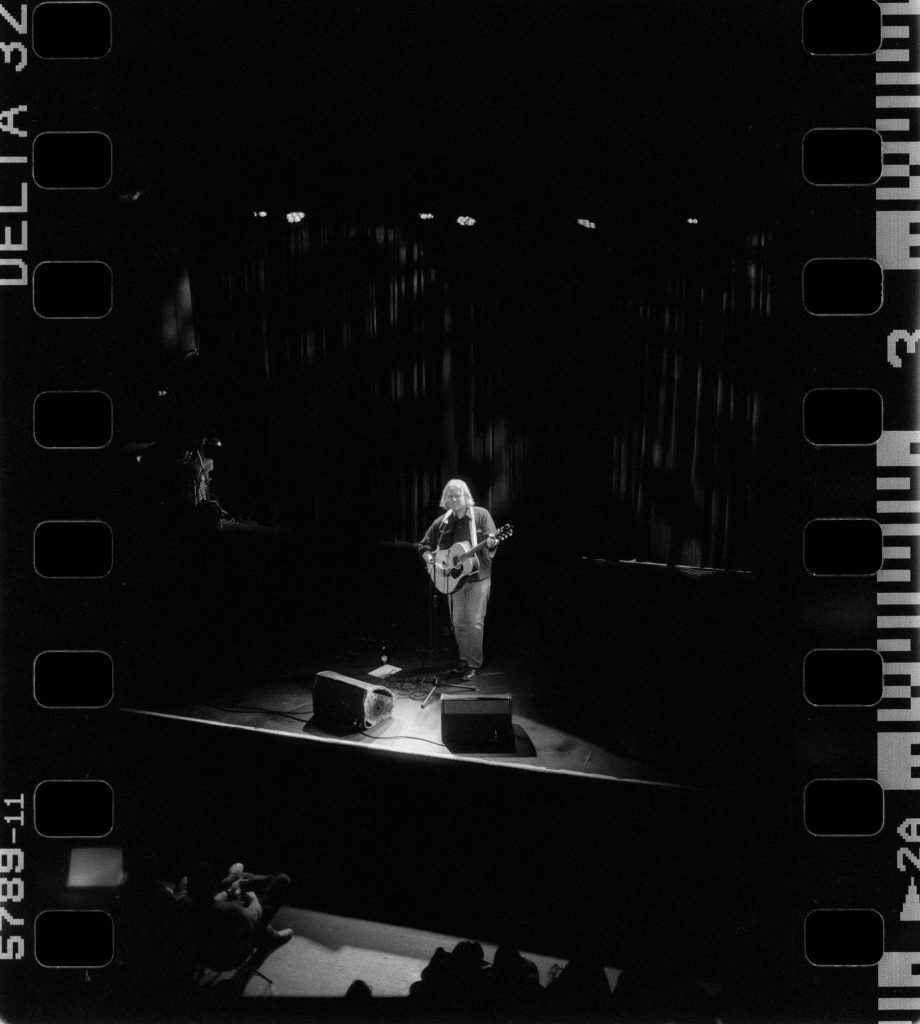

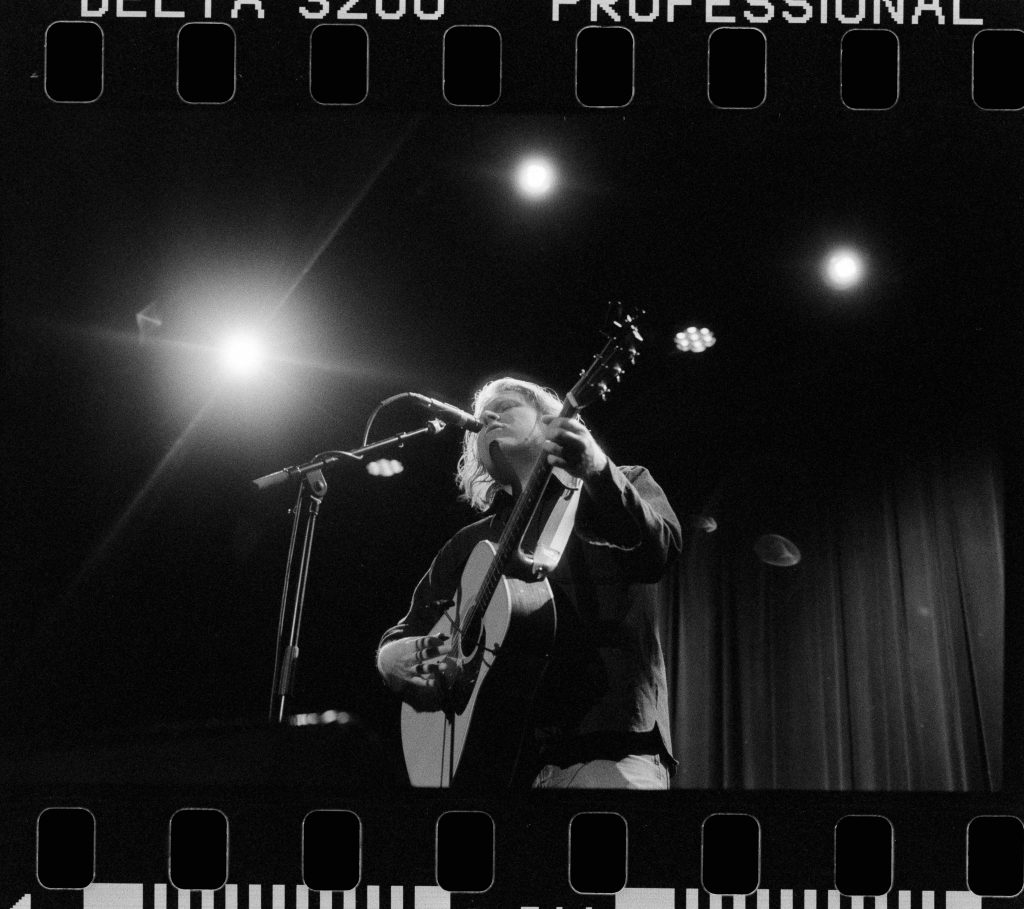

Ahead of his release of Possession, Segall embarked on a solo acoustic tour across the US, including a stop in New York at The Music Hall of Williamsburg. As a fan of his earlier, noisier music, I was curious to see how he would approach his catalogue in such an unplugged way. I had seen him before with a full band on his tour for Three Bells, which included a healthy but expected mix of old and new songs. This acoustic show felt like a show for fans familiar with the wide span of his discography. It was like a tour through his different albums, reinterpreting old classics like “Girlfriend” and “Finger” so that they worked solo, but maintained its charm. Even though I was sitting in the mezzanine with a couple hundred people below me in the theater, the rawness of Segall’s performance was like sitting around a campfire with him as he played my favorite songs. The show ended with 2018’s “Lady’s On Fire”, in which he completely commanded the audience. This was his sing along, as every hipster couple from Brooklyn screamed the song’s chorus with him. He had fun with it too, taunting the crowd by stopping abruptly right before every chorus of the song and cheekily grinning. It was a vulnerable performance, and listening to these songs being played in a completely different way felt like hearing them for the first time again.

Before his acoustic show, I sat down with Ty Segall to talk about Possession, playing music with his best friends, music “scenes”, and the video game The Oregon Trail. – Eamon O’Connor

Eamon: I want to ask you about the differences between Possession and Three Bells. Three Bells reminds me of a more dissonant sounding, Emotional Mugger-era, and this new one sounds new for you. I’m not sure if you have worked with horns and strings at this capacity like you have on this record.

Ty: The last time I did that was this record, Manipulator, but there weren’t horns on it, just strings. I’ve never really done horns and strings. On Freedom’s Goblin there were horns, so this time around I wanted to just throw in the whole kitchen sink. I think this is my version of a pop record.

When you’re writing albums, what guides the differences between sounds? Do you start writing with the intention of making a pop record or do you just start writing and see what happens?

I think it could be either version of that. Usually, you need to have a song or two before you make a decision like that, because if you make a decision like that without any songs, you probably aren’t going to do it. The songs push you in a direction and then you kind of pick the specific one. I think the songwriting helps decide that, but I wanted to make an epic pop thing on this one.

What was the first song you wrote on Possession?

Well a couple of them were kind of unfinished songs from other records, but I completely changed them, so I don’t know if that counts. But maybe “Shoplifter.” At first, I wanted to stick more to the idea of a cyclical thing, where you reuse the same riffs over and over again, I don’t know if you know that record, Smile, but the Beach Boys. The idea that I think [Brian Wilson] was working with a lot was, you introduce a theme, and then you use that theme in different ways. So it’s the same notes, maybe played or voiced a different way. I was flirting with this idea, and there’s a little bit of it, but I gave up on it. It’s a really hard thing to trick people that don’t notice it. It’s like playing the “You Really Got Me” riff on every song, people are like “Yeah yeah yeah, I get it.”

Did you want to incorporate this theme throughout the record?

I think that it ended up being that instead of one theme for the whole record it was each song would recycle themes in a song. “Shoplifter is one chord. And then a couple of different themes come in cyclically.

You mentioned Smile by the Beach Boys, what else were you listening to that inspired this record?

Some of my favorite records are the big lush records, Beach Boys’ stuff is big for me, but I think my favorite one of those kinds of records is Forever Changes by Love. Or like S.F. Sorrow by Pretty Things. Some would say that one is the bible of psychedelic music. Heavy hitters on that one. It was recorded in the same studio as Sgt. Peppers, it came out like a week after and it got completely passed over. But, I’m really into the LA-specific studio early 70s stuff, like [Harry] Nilsson.

I watched a video where you were talking about that Love record and you said it took a while for it to grow on you. Do you find that the records that become your favorite records are the ones that are maybe shocking to you and take a bit to grow on you? I feel that way. A lot of my favorite records are ones that I didn’t understand at first.

Well yeah, no I definitely feel like a lot of my favorite records grew on me. Some were just immediate. But, for instance, Funhouse by the Stooges wasn’t my favorite Stooges record when I was a teenager, but now it’s my favorite one by far. Forever Changes wasn’t my favorite Love record, I was more into the raw ripper stuff.

Miles: You mentioned that S.F. Sorrow is considered to be a bible to some, what would you say is your musical bible?

The first four Black Sabbath records, Forever Changes, Funhouse by the Stooges, Damaged by Black Flag, the first Madonna record. There’s too many, but those are the ones I’d say are perfect records.

Eamon: For this new record, you wrote it with a really small group of people. You’re playing most of the instruments on it, and you’re working with your friends Matt Yoka and Mikal Cronin. How did you start working with them?

I’ve known Mikal since I was 15, we went to high school together, so we’ve been playing music together for 22 years. I met Matt when I was 18 or 19, we went to college together, and we’ve just been making weird shit ever since then. It’s cool with Matt because he doesn’t come from a musical space, he’s a film-maker. I was trying to make lyrics for the songs come from a different place so I just had the idea of writing with him because he’s got a cinematic mind. He’s a different kind of storyteller from me. My lyrics are more inwardly surrealistic and weird.

You have had different eras throughout your career, and throughout the different eras you will tour with different bands. With the Freedom Band coming to an end, what’s next? Who will be in the new band?

Well we’ve done a tour already. That band was so established, that if anybody left, it just wasn’t that band anymore. When Charles left, we got Evan Burrows to play drums now. It’s the same band but with Evan. I don’t think we’re gonna have a moniker for the band. I haven’t really come with a good one yet.

Going back to the lyrics on Possession, is there a theme that connects the stories together lyrically?

There is. We were trying to write stories about people, and were thinking about “Where are these people? What’s going on?” and it turned into these American stories. Some of them take place in different times, like a couple hundred years ago, some of them are modern, but I think that all of them can be taken into a modern perspective. So we ended up being like “Let’s write about what we know.”

Is there a story on the record that stands out to you in particular that you like the most?

Well, I do like the brutality of the song “Alive”, which is about the Donner party.

I don’t know what that is.

It’s a family and group of people that got snowed in making their way to California, and they ended up having to eat each other. My wife is from down the street from where that happened. I’ve driven by it a bunch of times. It’s a really weird thing. We were talking about manifesting destiny and people battling nature, and how nature is always going to win. I thought it was fun to write about. Nature is gonna take you down, man.

Miles: It’s funny that you say that you’re writing what you know and then citing the Donner party, but then your wife is from down the street so you really are just writing what you know.

Yeah I’ve been up over there a lot of times.

Do you think you would survive?

No.

Would you even go?

Oh my god, a few hundred years ago, do the Oregon Trail? Hell no. That’s crazy. Well maybe I wouldn’t go because I’ve played the video game and I know what happens.

Eamon: I love that video game. I think I died of dysentery every time. What guitars are you playing right now?

On this tour I have a Martin, acoustic, D28 which is really great. But at home, I have my trusty Les Paul, and I have my SG. But I actually just grabbed my old ‘66 Mustang, and I’ve been messing around with that thing. I think it’s time for me to get back into Fenders again. It’s what I used to play forever.

So this is a Gibson record?

Yeah.

Miles: How do you decide what to use?

Well they all sound a little different.

Do you think that you start off with one of the songs on a certain guitar and decide to stick with that guitar for the rest of the record, or is it a conscious decision you make before to play a specific guitar.

It’s like a paintbrush. They all paint in a different way. Pedals and the colors and the guitars are the paintbrush, and the song is the canvas. I didn’t want to go extremely nasty on this record. The Les Paul is really blown out and nasty, and the SG is one notch dialed back, so I used that most of the time.

Eamon: Going back to the recording of the album, did you have any weird recording technique you used?

I wouldn’t call them weird– I think I was just trying to go classic. With the budget I got to buy this crazy microphone. I had a stereo pair of these mics called U67s, they’re Neumanns, they’re like the gold standard from the 60s and 70s, you look at a photo of Bob Dylan, and he’s got a U67. So I used those to do the Glyn Johns drum recording technique, which is like Let It Be, a bunch of The Who records, a bunch of Stones records. So I got to do the thing I’ve always wanted to do for the drums. And then I’d blow some shit out if I wanted it blown out. I didn’t do anything super weird.

I watched an interview where you said you love music that comes from a specific scene, whether it was Soft Machine and the Canterbury scene or Eno’s No New York. Considering your vast and diverse career, what scene do you think you would fit into nowadays? Do you think scenes are something people think about while it’s happening or after the fact?

I think I’m more affiliated with the San Francisco scene than I am with the LA scene, just because it’s where I cut my teeth a bit, and started doing stuff. I’m more affiliated with Thee Oh Sees and Sick Alps and other San Francisco bands. I’m still close with those people. I think LA has a different kind of scene, and it’s a little bit wider and sprawling. I think I’m less in a super tight-knit scene now, but that’s not necessarily true–because it’s more just like all of our friends. But I don’t know how people view that, which I think is more of your question– and I do think that people view it afterwards. I think that the San Francisco thing was a bit more of a scene. I think now it’s less of a scene.

Miles: Do you think that having a smaller community rather than something more spread out or sprawling affects your music in any way?

Yeah! The cool thing about San Francisco– and I’m not saying this about LA fully, because I live in and love LA–but in San Francisco it seemed like musicians really just were making shit to make it. There was no expectation of anything. There is a little bit of “LA is an industry” just like in New York and so there is a lot of that thrown in as well, so there’s a lot of… I wouldn’t say people trying to make it, but I guess a lot of industry around. And there is no industry like that in San Francisco, it’s just a bunch of weirdos making music. And it’s a way smaller town, way more tight-knit scene so I do feel like that just makes it a different thing.

Eamon: Let’s talk about your new band, Freckle. Who is the other half of the band, Corey Madden, and when did you start working with him?

Corey is this great guitar player, songwriter, singer. He moved to town about 5 years ago, he has a band called Color Green. He’s a great dude and we just wanted to make a weird fun record. He would slowly start coming over to my house and we would just make weird shit.

Do you have plans to play any of that material live?

We’ve played one show.

Miles: Do you feel like you have learned anything new from starting a new band?

Well, I’m always trying to learn something new, you know? Until I die. Or until I want to stop playing music.

What would you do if you weren’t playing music?

I would go back to school and study philosophy… and not be able to get a job.

Eamon: When you’re writing songs for your many different bands, do you ever have a hard time deciding if it’s going to go on a Ty Segall solo record or on another band’s record?

No. If I’m writing a song with Corey, then it’s a Freckle thing for example. Back in the day, I brought a few songs to Fuzz, but not usually. I usually know where it’s gonna go.

You scored a film semi-recently for Matt Yoka’s documentary Whirlybird. Is scoring films something you would want to do again?

Yeah, I’m actually working on something now. It’s a narrative feature film.

We’ve talked a lot about collaboration and you’ve talked about how collaboration is really important to you, and considering you’re currently on your solo acoustic tour, I’m wondering what are your favorite parts about playing and touring with a band, versus doing it solo?

The band is just amazing because you’re just playing with your friends. I’ve never been in a band where I’ve played with hired guns or anything like that. All of my bands have been really good friends of mine. I don’t ever want to do that, I feel like if I had to do that, I would just quit, because it’s like, “What’s the point?” I’ve been really lucky. It’s always been a really good time with people I really love and have a musical hive-mind with. Everyone’s taking risks and you’re there with a safety net–and then it’s your turn to jump off and try to land it, and someone’s there to catch you if you fall. You can get places with a band that you never, ever, ever, come close to getting to by yourself, but the solo thing is really cool because it’s the big test of the song. You get to see if the song works. I’m not saying that a song has to work in this setting, but it’s pretty cool if it can. It’s almost a thesis.

Do you think it’s just as fun to play on stage to play solo?

No. It’s not really even about fun. It’s a test. It can be really fun, but oftentimes it’s less fun, or like you’re just battling yourself. It’s like an ego death. You’re fighting your song.

Do you think that your more heavy, nasty, songs work in an acoustic context, or do you usually gravitate towards more softer songs you’ve written?

T: No, the heavy ones work, you just have to maybe flip them upside down. Sometimes the mellower ones are the most boring.

You have taken on a more executive role in recent years with GOD? Records and Harmonizer studios. It reminds me of how John Dwyer and Castleface records were early supporters of yours. With this new executive role, do you see any new comers that you think are up next in the future of guitar music?

That’s a heavy thing to say about anybody. I think there’s a lot of people. Someone made a good point the other night– the bigger Taylor Swift gets, the more space there is for something crazy and heavy and weird to get big as a reaction. So I’m thinking it might be time for something weird and crazy to get big.

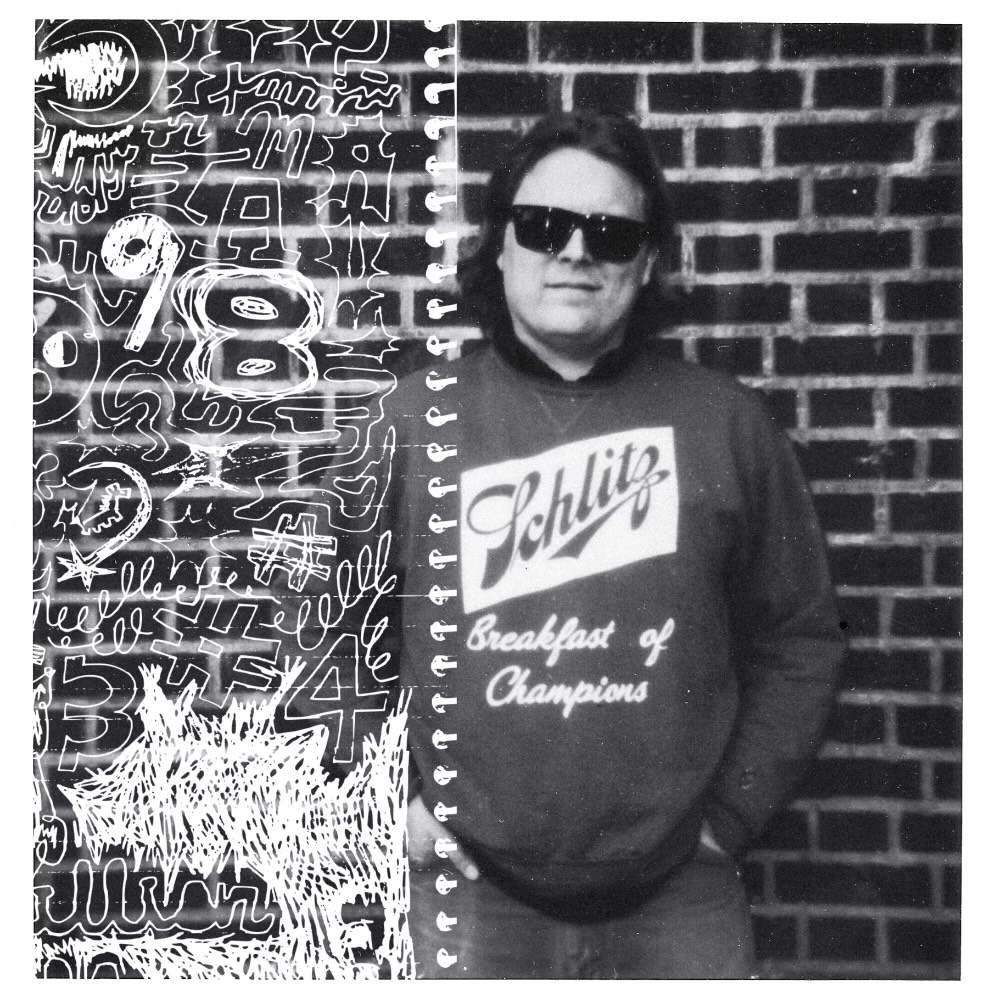

Editorial Photos by Miles Ellisor