It wouldn’t be entirely incorrect to say that, nowadays, most folk festivals still around heavily rely on co-opting the entire genre of folk for their own capital, sanitizing the term down to a point of unmeaning by fronting music with an overly nostalgic, spectral connection to either Bob Dylan, protest picket signs, or sappy love songs. Especially in a city like New York, which in yesteryear’s Greenwich Village housed the core of the folk renaissance in the 1960s, there aren’t that many Downtown spaces left for folkheads to linger that aren’t either wholly awash in the effects of gentrification or simply just gone altogether—disappeared space and culture left to be romanticized in a bland biopic.

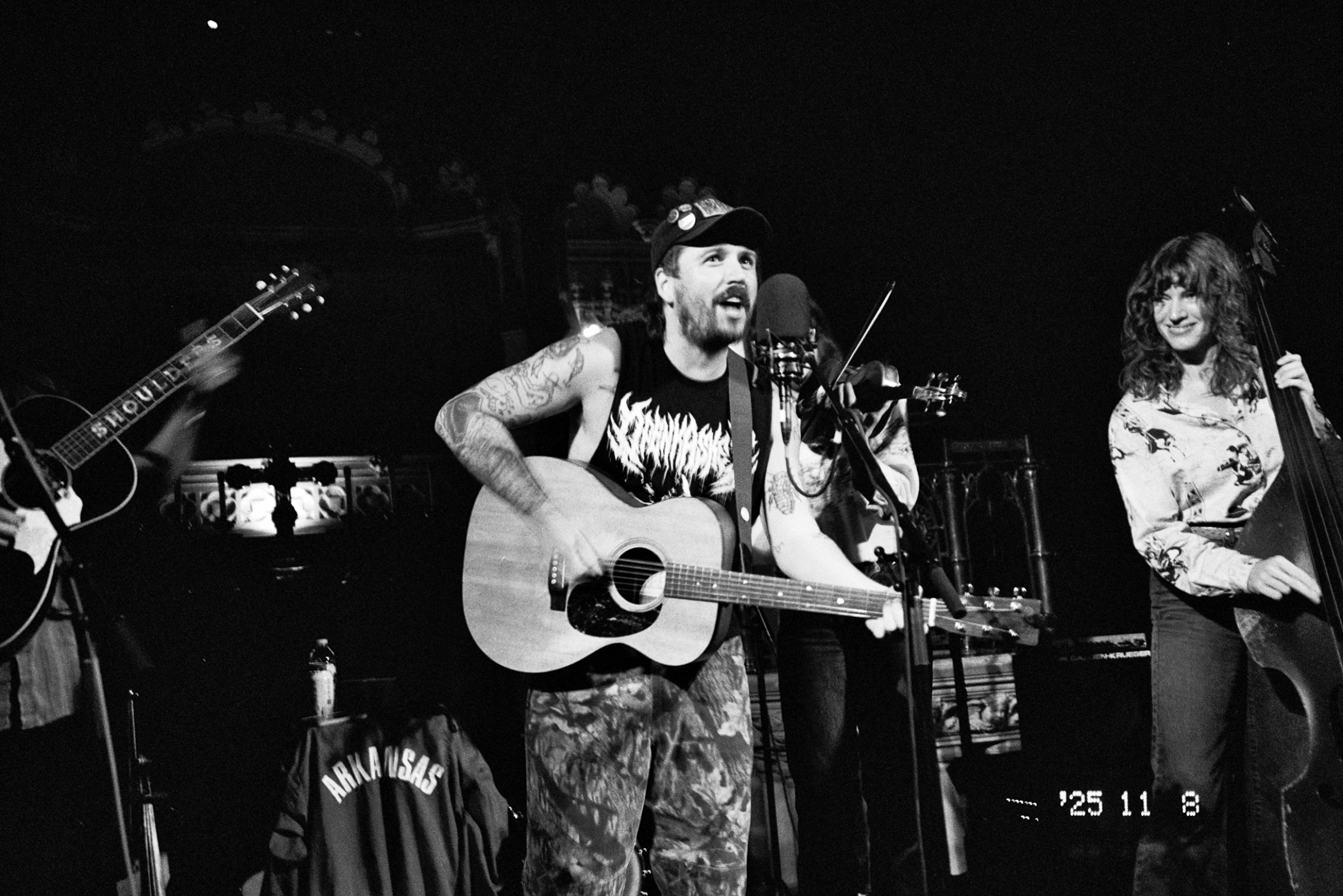

But the 17th annual Brooklyn Folk Festival, put on by Brooklyn’s folk label Jalopy Records at St. Ann’s Church in Brooklyn Heights from November 7-9, skirted the plague. Unlike, say, Newport Folk Fest, where in 2025, you could’ve paid 300 dollars to see indie-rock headliners Geese and Alex G, Brooklyn Folk Fest remains diverse, local, and heady; there is barely an entrance fee, and no emphasis on what’s capturing the attention of the current zeitgeist. Its rich and lengthy lineup casts a wide net across every folk distinction you could imagine: from singer-songwriter acts like Angela Autumn and Allegra Krieger, to the Rising Stars Fife and Drum Band, to the local Ukrainian Village Voices choir collective. It’s the type of event that lives up to the history embedded in its name; outside the church, immediately upon walking in, a troubadour was covering Gillian Welch, and inside, a 57-person banjo band played on stage. There were literally no other instruments—only banjos, played in tandem.

In the festival’s 16-year history, founder Eli Smith has gone out of his way for nearly two decades to produce a dissident lineup featuring a particular subculture in New York, full of folk acts that honor the genre’s forefathers in all respects and varied interpretations. Smith was raised as a musician in Greenwich Village and performs both solo and with the group Down Hill Strugglers; he’s even opened for Patti Smith and Steve Earle.

“Blues, string bands, and more are the definition of old-school folk music,” Smith said over email. “That’s one thing that is very important to us at the festival: to make sure that these historic forms of American folk music, as well as music from all around the world, are showcased at our festival. We think that the long human tradition of expression through music, folk music, is the well from which contemporary creation draws. Nothing is really new.”

“It’s so great that Brooklyn Folk Fest is not just a bunch of white guys on stage with acoustic guitars, because, unlike what people think, that’s not everything folk music is,” New Orleans-based musician Chris Acker said.

“For right now,” he jokes, “I’m unfortunately going to be one of those guys.”

Acker performed a standout set of the weekend; both sardonic and charming, his folk music is just as traditional as it is a bit odd. He sings wry spoken-sung lyrics that simultaneously break your heart while making you laugh, such as when he imagines his ex-girlfriend’s new partner rubbing aloe vera all over her, post-sunburn. “When the sunlight kisses her warm skin / Hope it directs its attention to burning him,” he sings, then pauses mid-song to interject, “if you are rooting for me right now in this song, you probably shouldn’t be.”

I’m not entirely sure yet the significance of putting on a folk festival during a time like the one we are all in, where streaming platforms release fake AI songs under the monikers of dead artists and countercultures have been commodified so much that something like Noah Kahan’s brand of folk has begun to more closely resemble white, wealthy transplants living in Bushwick than homespun music, progressive politics, and anti-establishment actions. Still, it seems as though the world hasn’t yet swept up the entire genre, as nearly every band I watched at the festival spoke at length about what it meant to be part of the ongoing folk tradition, where politics are inseparable from the music.

“I wrote this song about resource hoarding and the Billionaire class,” Kaïa Kater, the lead vocalist of New Dangerfield, said while introducing the band’s set. New Dangerfield is a Black string band formed in 2023, who are “on a mission to liberate the Black string band tradition,” playing folk festivals and fiddler’s conventions across the country to antidote the erasure that Black roots bands have had in public music knowledge. The band headlined the festival on Sunday evening at the church’s main stage, where many in the crowd ended up standing up out of their seats, and waltzed for the majority of band’s set. “Resource sharing is the only way out of this mess, and it’s about neighbors helping neighbors. And I really feel that here in New York, in front of all of you.”

It was also on Sunday afternoon that a woman simultaneously danced and sobbed next to me. She was watching Peter Stampfel begin his set. The woman sung along as Stampfel played the fiddle among a large acoustic ensemble of musicians who were, at the very least, three decades younger than him. Stampfel also joined the stage Sunday night for a tribute set to Hurley, who passed away at his home in Oregon in April 2025, and is remembered for his eccentric genius in the underground Greenwich folk scene, often referred to as the godfather of “freak folk.” Hurley headlined the festival just last year.

Stampfel was at the heart of the Greenwich folk revival in the 1960s, even sharing the stage with Hurley and Dylan. Though, he may actually be best known for founding the culty, psychedelic, electric-acoustic folk duo, The Holy Modal Rounders, in 1963 in Manhattan’s Lower East Side, who totally upended purist folk and upset folk traditionalists everywhere. After a rocky four decades of drug addictions, public breakdowns, and an incessant falling out to reunion cycle, the band broke up for good in 2003. Now, at 87, Stampfel is still singing protest songs about Elon Musk’s evil and the corruption of the billionaire class, and strums long, verbose songs about dancing in kitchens and driving through Texarkana with his partner.