The Hellp, the nine-year electro-rock project between Noah Dillon and Chandler Ransom Lucy, has been teetering on the verge of virality since its inception. Dillon and Lucy had no lifelong dreams of musicianship. Both were raised in rural pockets of the Western U.S. and share pasts of working odd jobs at grocery stores and construction sites, arriving on the L.A. arts scene as rookies of photography (Dillon) and modeling (Lucy). The two met by chance at a photoshoot, neither possessing any musical experience, and established the project out of a fear of “dying without ever being in a cool band”.

Though the lore behind them is eccentric (and maybe obtrusively self-mythological), their style and approach follow suit. Since 2016, their music has expanded and refined across genres, eras, and mediums, the rules of their sonic and aesthetic worlds continually pushing their own limits. There is no marketable “Hellp” sound; this is perhaps why even their biggest hits like “Tu Tu Neurotic” and “Ssx” haven’t gone measurably viral, but the lack of cohesion makes room for experimentation and evolution that few bands of their strain have the freedom to undertake. This is likely influenced in part by Dillon’s “hyper-religious” childhood and lack of engagement with secular media until age 18, and it’s entirely to their artistic benefit.

They claim their music is distinctly “American” and draws influence from a kaleidoscopic array of American artists from Bruce Springsteen to A$AP Rocky, but the portrait they paint of the country is fueled by exoticism and skeptical detachment. They’re natural outsiders to celebrity culture and niche witnesses to the American experience, offering an external eye held before by non-US artists like Lynne Ramsey and Jacques Demy; through this lens, the American spirit contorts into something bigger, more romantic, and vibrantly exaggerated as it’s infused into and commemorated in the work. This externality is invaluable, placing a much-needed finger on a national pulse that pop music continuously forces itself onto but rarely meets with honesty and color.

Their online reputation precedes them at times, with sparing but often harsh video interviews making up the majority of exposure they’ve received as a project. Their internet personae have been branded as arrogant, pretentious, and bombastic, the band notably proclaiming their music is some of the best released this decade, the duo itself being the “last cool band on Earth”. While their absence in the media and compact venue sizes on their fall tour may raise questions on their traction, the duo has received co-signs from some of the world’s biggest artists like Frank Ocean (who had their “Confluence” music video on his Blonde moodboard) and Kanye West (who reportedly played their song “Beacon 002” on his private jet).

As the duo has distilled their work and image, spending years reworking and perfecting tracks based on their evolving tastes and expectations, audiences and industry figureheads have begun to take notice. The band signed to Atlantic Records last year, a titanic step in their ten-or-so years of shuffling progression. Though, per usual, The Hellp was cryptic about release plans since their Atlantic deal, they quietly rolled out a string of singles late last summer before dropping LL, their debut studio album and a compilation of tracks with origins as far back as 2018.

After hosting the premiere party for their single “Go Somewhere” at The Hole on Bowery, the band returned to New York in November to play a sold-out show at Irving Plaza. They’ve played a handful of New York shows since 2017, but this tour was by far the most cohesive and broad they’ve had, especially following the landmark of a debut record.

By the time doors opened at Irving Plaza, the line stretched three blocks around the venue with attendees all donning a fairly cohesive array of dark, tight costuming somewhere between Rick Owens streetwear, kink gear, and late-2000s grunge pastiche. The origins and inspiration didn’t appear homogeneous (the outfits were far more extravagant than anything Dillon and Lucy are known to wear), but everyone seemed to get the memo – deep blacks, sleazy fare, and subtle hypersexuality. Though the dress code made visual sense for the fandom’s young, alternative demographic, it clashed entirely with LL’s sensibilities–rarely verging on grunge and avoiding explicit content. Not a single song on LL contains profanity, and very few feature any nods to sexuality. Dillon seems far more occupied talking about “neighborhoods” and “suitcase reporters” than details of intimacy and relationships. Most lyrics are so vague and nonlinear they strike as anonymous and out of time, and the imagination could just as easily pin them to any angsty suburban high-schooler as a rockstar in the hills of L.A. With the new album and its accompanying visuals, the duo has crafted iconography at the crossroads of these extremes (perhaps best showcased in their “Caustic” music video, an endeavor six years in the making), curating a brand of new wave Americana that audiences seemed yet to widely embrace.

The crowd’s leaning toward sleaze and debauchery could be best explained by the music’s sonic content, especially the new album, which rarely takes a breath in its aggressive tempi. Most tracks end with distorted contortions of their own sounds that lead seamlessly into the next song’s hyperspeed melody, a musical barrage in ceaseless overdrive. Tempi rarely dip under 140 beats per minute, with 120 being a fairly standard pace for dance music. It’s beautifully overwhelming and constantly reinventing itself, some songs practically self-remixing at their midpoint in avoidance of static repetition. Each individual track exhibits a microcosm of The Hellp’s career, evolving with taste and technology and never doing one thing twice, with energy often pushing physical bounds. The music buzzes with friction and collision and sports a miraculously high libido considering its chaste lyrical content and Dillon’s oft whiny, boyish delivery. The costuming of the crowd made clear that its members were, if nothing else, ready to sweat.

But as the audience packed Irving Plaza’s second-floor auditorium, bodies were still, beers were 15 dollars, and conversations clunkily bounced around topics like Nettspend, couture fashion, and Slavoj Zizek. The attendees dropped their grimy, ne’er-do-well facade and embraced familiar chronically-online talking points, if socializing at all. At one point, a member of the audience vomited in the center of the theater and rushed out. Instead of brushing it off and championing grit in the vein of the 80’s St. Marks punks who appeared to be the crowd’s aesthetic predecessors, the leather-clad mob wore sour faces and kept an arm’s length from the mess until a team of custodians came to clean it up. It became clear that Dillon and Lucy were not harboring transgressors or scene-shakers themselves but reactions to reactions under layers of abstraction, cosplaying a figment of a more colorful era.

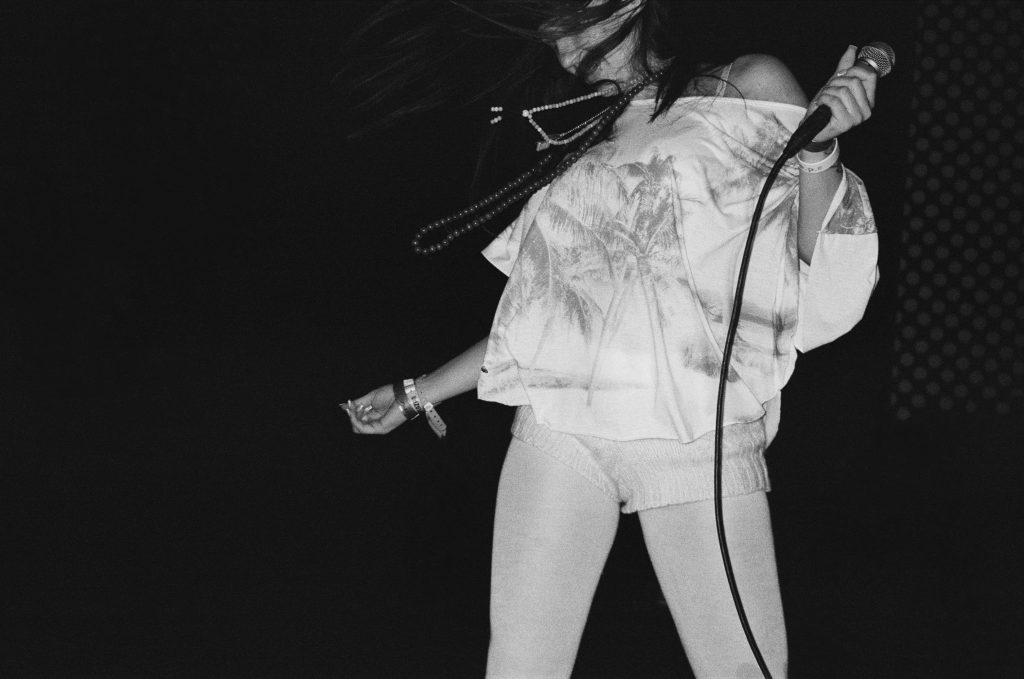

London-based duo Bassvictim, with their second ever performance in New York, opened the show shaking the walls with hedonistic hits like “Flop” and “Air on a G String”. Frontwoman Maria Manow oscillated between justified rants that playback was too quiet, strobes were too weak, and the venue should “treat openers right”, and sprees of smoking on stage, crowdsurfing, and leaning over masses crushed against the barricade while she sang against distorted, dissonant dance tracks. Joining her on stage were renowned scene photographers Matt Weinberger and Mark Hunter aka Cobrasnake, whose sporadic flashes marked the show as a cultural affair worth digitally immortalizing and inevitably tied to New York’s currently precarious downtown scene.

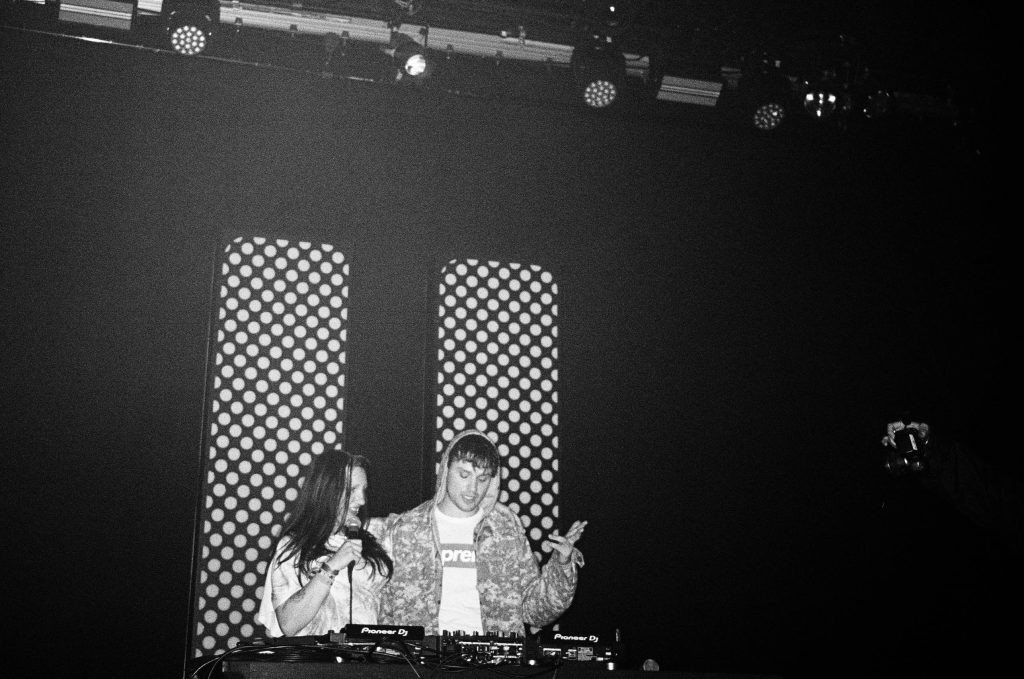

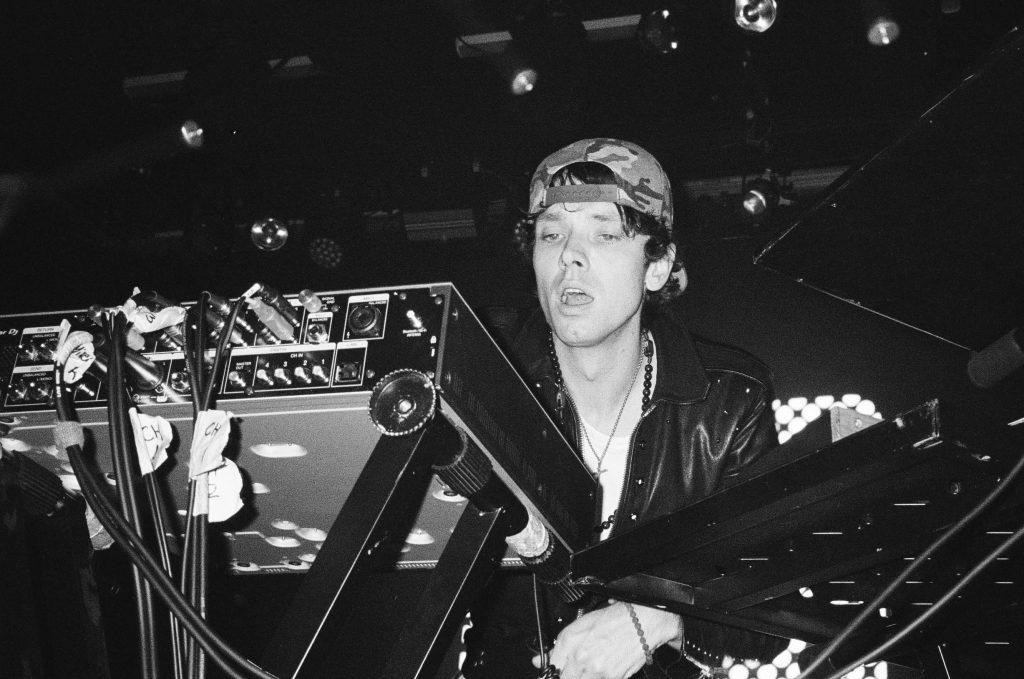

The Hellp began their set shortly after, the stage sparsely decorated with two illuminated beams and tech tables for both Lucy and Dillon. The duo was backlit by the beacons in the otherwise darkened space, save for the occasional blasting strobe from above. They hunched over their gear, Lucy equipped with synths and mixers, Dillon primarily using a single delay pedal to warp sound into unintelligible cacophony. Between songs, Dillon would use the pedal to drown the theatre in infinite, thrashing reverberations of his own voice that silenced the crowd in deafened awe and anticipation for the next kinetic needle drop from across their discography. Throughout the set the two became anonymous leather-wrapped profiles, their shaggy hair covering what was left to see of the faces they mashed into their equipment. The audience paid no mind to the lack of theatrics, meticulously singing along to every ASMR sample and vocal glitch across their 14-song set.

They closed out with a transcendent mashup of their biggest hit, “Tu Tu Neurotic”, Lady Gaga’s “Just Dance”, and Miranda Cosgrove’s cover of “About You Now”, strobes still flashing, audience still vigorous and entranced. As the audio descended into a final roaring noise loop, the duo came out from the darkened grotto and stood against the barricade, looking out into the audience for perhaps the first time during the set. They greeted front-row fans with hugs and transparent joy before exiting backstage. For an act presumably so dedicated to their detached joint persona and hypercool elusivity, it offered an endearing crack in the meta-rockstar facade their reputation has erected for them.

Dozens of audience members lingered behind steel barriers stationed outside the venue, smoking and debriefing and waiting for the chance to meet the duo. Fans fumbled around for anything to sign, settling on cigarette packs, rolling paper folders, and the merch they were wearing when Dillon and Lucy walked out of the venue and into the crowd. Both were particularly excited to sign someone’s cream Margiela jeans, an autograph on each thigh. They spoke with every fan who waited for them, Hunter and Weinberger sticking around to flash photos of the conversations happening across the barricades. Somewhere in the middle of this stretch, a man who called himself their “sort-of manager” came behind the barriers to play a demo collaboration between Dillon and Ecco2k off of his local files (while performatively swatting away phones trying to rip the audio) in what could’ve easily been a stunt to build hype and enrich lore around the band. While it wouldn’t be out of character for The Hellp’s aggressively online industry peers, Dillon confirmed in a short interview follow-up the following night that the track will remain in the vault indefinitely to avoid ripping “clout” off Ecco, an artist the duo has shown great admiration for.

“You guys fuck with the album or no?” Dillon asked, deadpan. Met with shock and affirmation from the crowd, he added, “I don’t know, it could suck.” Whether searching for gen-pop commendation or honestly acknowledging a lack of confidence in his output, his humility was disarming and legitimate, especially considering LL’s only reviews online (then and now) were a Pitchfork article released only days before and a few fan assessments on Album of the Year. Though signed to one of the industry’s most powerful labels and with years of national tours to their name, The Hellp and LL are virtually MIA on all major music publications. With newer artists of similar status like Fcukers, Snow Strippers and 2Hollis showing up on the largest major festival lineups in the world, it’s even a mystery to the band why the industry has offered them little more than radio silence.

Dillon took to Instagram upon the release of the 2025 Coachella lineup, on which all aforementioned artists are featured, stating “hilarious we aren’t playing Coachella – this industry has always looked the other way – Meanwhile the very sounds they book are a direct by product of of [sic] our contribution”. The Hellp seems built for festivals like Coachella. Their music, when the glitch and filigree are stripped, falls neatly into electronic and dance slots, their sets are minimal, and their brand is hot amidst the indie sleaze revival, a movement they crestfallenly credit themselves with popularizing. But there seem to be forces at play beyond the band’s sound and image which keep them from the musical milestones their contemporaries have enjoyed in recent years.

“Do you think the industry or the media or festival promoters are scared of you guys?” I asked Dillon outside the Plaza. “I think so, I think so,” Dillon replied, “we’re flagrant, and in our interviews we just say random shit, so people are a bit afraid of that, and you know, unless you’re packaged correctly and a safe bet the industry will reject you, more or less.” But the impudent laxity Dillon mentions, seen in their 2023 SXSW interview, recent conversation with the Ion Pack, and beyond, doesn’t extend to the work itself. Impulsivity and brashness are replaced by burdening perfectionism and long gestation periods.

“Real artists, like ‘All of the Lights’ by Kanye, it took him 6 years to make,” Dillon said, “so, if you have a good idea and it lasts 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6 years, you know it’s, like, actually a good idea. Like, ‘Sinnamen’, we put on the record, I feel like it’s still as relevant today as it was in 2019, so I think patience is very key and that will show you if something is like an omen or iconoclastic, like canonically.”

After years of sparse output and secretive creative processes, The Hellp’s fans champ at the bit for new music in any form. Ten second clips of unreleased tracks ripped from Dillon’s and Lucy’s instagram stories are scattered across YouTube and Soundcloud, as are the scrapped albums the duo intentionally pulled from streaming to curate their catalog and manicure their narrative. Though these acts of fan insurgence wreak havoc on artists of their ilk, sometimes prompting aggressive legal action, piracy isn’t the prime issue the duo find themselves facing.

“I guess it enhances the lore, but honestly I hate how people talk about us,” Dillon said, “I go online for like two seconds and it’s just the most asinine, ignorant comments. I guess we’re easy to hate, like, whatever, I get it, I’d probably hate me too, but still, it’s very disheartening and it makes me want to quit all the time.”

This isn’t the first record of Dillon threatening to quit the band and the industry altogether. Across social media, he’s spoken on his shortening fuse for what he sees as dismissal and mistreatment from fans and industry figures alike, one time posting a screenshot of LL’s “Halo” to an Instagram story with the ominous caption, “you’re going to miss us only when we’re gone”. Whether or not these claims hold water, they speak volumes on the laughing stock made of even deliberately genuine artists by meme and commentary culture.

In December, meme page @still_on_a_downward_spiral posted a text image reading “Lord the men u put on this earth to hunt and provide are wearing size 28 women’s flares and listening to The Hellp”. The meme was seemingly posted in good fun but sparked a digital retort from Lucy, saying “I can’t believe you guys have taken probably the most sincere and honest music project of the last decade and cannibalized it into this weird posturing of nonsense”. The message lies at the crossroads of self-aggrandizement, creative sensitivity, and perhaps further layers of irony in itself, but is an apt response from a band that never knows precisely where it is or what it stands for, creating and reacting primarily on aesthetic grounds and devoted the abstract idea of the “future of art”.

In this future landscape, more than their glitch-rock sound or monopoly on leather jackets, the duo wants to be remembered for the sincerity of their output. “It’s just authenticity,” Dillon said, “we’re very earnest, no matter what anyone’s been saying about us online or what they think, like, we really take this shit seriously and we try very hard to make beautiful things that will last. That’s all we’re trying to do. Everyone can resonate with that. People love when someone’s actually real, and that’s what we are. That’s not saying like WE’RE REAL, but like, we’re kinda fucking real.”

The following night, The Hellp and Bassvictim, joined by Ren G, held an “afterparty” at Market Hotel, each act playing an hour-long DJ set for a small mob of familiar faces from the Irving Plaza show. The fog was thick and blinding, making hazy silhouettes of Lucy and Dillon as they played cuts from their discography between tracks by Katy Perry, Tove Lo, XXXTentacion, even a glitched-out Jersey Club remix of “HOT TO GO!”. Through the smoke, though, when Victoria Davidoff’s vocals from LL’s “Shadow” began and the crowd chanted along, I could make out a smile breaking through Dillon’s brooding glare. With nothing but the edges of the deck separating them from the audience, their commitment to their costume of dark swagger and stylized detachment was threatened but in full swing, reminiscent more of performance art than bona fide braggadocio.

After the set, I stopped to talk with Dillon and a videographer from the Plaza show. Dillon surveyed my thoughts and audience assessments from the night before–if, during the show “it looked like [he] hated it,” if the backlighting scheme meant to obscure their faces was successful. The “douchebag in jeans”, the digital rockstar was replaced by a neurotic battle-of-the-bands contestant hoping his passion project worked out on the big stage. A passing crowd member asked him if he’d ever release a song in the vein of “Wingspan” again, a noisy, purist indie-rock track that popped up on projects for five years before its official release in 2021. Dillon feels that the band “struck gold” with the song as a genre experiment, but he’s never found himself using electric guitars in a mode as stimulating or masterful since, so he’s dropped them from the band’s sound. Right now, he believes the band’s electronic production is its most cutting edge endeavor, so they’re leaning far into it until, perhaps, they move on from the genre as well.

LL speaks truth to this self-appraisal. The album’s most notable innovation, beyond its hyperactive beats, blown-out synths, or arena rock callbacks, is its use of silence. In nearly every track there are explosive moments where instrumental feed is cut into a spare beat of beautiful, crisp nothing, reminding listeners of the void their high-octane sound is filling. Before audiences can catch their breath, in Irving Plaza and beyond, the blazing stimulation charges on. In these pauses, time goes on and the world’s ambience still resonates. In between singles and album cycles and threats of quitting the game entirely, these silences grow longer and starker, but they offer listeners space and clarity to bear witness to electronic music’s and greater pop culture’s progression in the band’s direction. Though the cultural moments and movements they claim to have sparked aren’t popularly attributed to their output, it’s always only a matter of time until listeners discover the bright source of musical progress grinding against domineering algorithms.

Dillon spoke to this in an Instagram live this past September. “When we dropped ‘Tu Tu Neurotic’ nobody liked that song”, he said, “it took three years for people to realize it was ‘their entire identity’”. The song features tweaked out, flashy vocals from Dillon reminiscent of mid-2000’s racy hip-hop duo 3OH!3, Eurythmics-esque pulsing synth bass, and a dirty, thumping beat that still sounds fresh. The culmination of these disparate elements renders a timeless quality that Dillon believes went over listeners’ heads when the track was released in 2018. “We always make things that people don’t want yet, until a few years later [when] someone comes along and drinks up the milkshake.” There is a historical precedence for the large kernels of truth in The Hellp’s self-prophecies. Looking into 2025 and beyond, despite Atlantic Records’ and the general industry’s lack of a pedestal for LL, despite the band’s constant contemplation of ending their run, one can faithfully foresee their sound and style continuing to steer American taste and culture. If Dillon’s bets are right, we won’t recognize their influence until they’re on to the next sonic and stylistic frontier.

“Just living in the moment, dog, like that’s it,” Lucy professed at Irving Plaza, “if it’s cool then, it might be cool later, if it’s not cool later then fuck it, make something else.”